If you want to go viral on YouTube, a popular way to do it is by filming college admissions results. In YouTuber Kyle Tsai’s video, which garnered over two million views, he films his reactions to various application results from 23 of the top universities in the country, including Harvard, Princeton, Stanford and more. Fortunately, Tsai achieved incredible success in the college admissions process and is currently attending Princeton. However, the admissions strategies exhibited in videos like these damage the college admissions process and illuminate a dangerous truth about Generation Z’s extreme focus on success.

“I applied to a whopping 16 colleges,” freshman Dominic Gibb said. “I knew I wouldn’t be going to some of them, but I just applied to have as many options as I could.”

At the end of the day, each student applying to college settles on a single school. So when students are applying to 16, 23 or 55 colleges (as current University of Southern California student and YouTuber Badruddin Mahammed did), they sequester spots from other students.

Some waive off this argument as based on circumstantial evidence, but the facts tell a different story. University of Miami’s application metrics skyrocketed just in the last year. UM’s 2020-2021 school year saw a 28% acceptance rate of roughly 42,000 applicants. Compare that to this year’s acceptance rate of just 19% of 49,000 applicants. The drastic shift in these numbers is due to the quantity over quality mentality that is pervasive among applicants. Although some argue that the overwhelming numbers can be attributed to natural population growth, census data disproves the theory as just 23,000 more kids were born in 2004 than 2003.

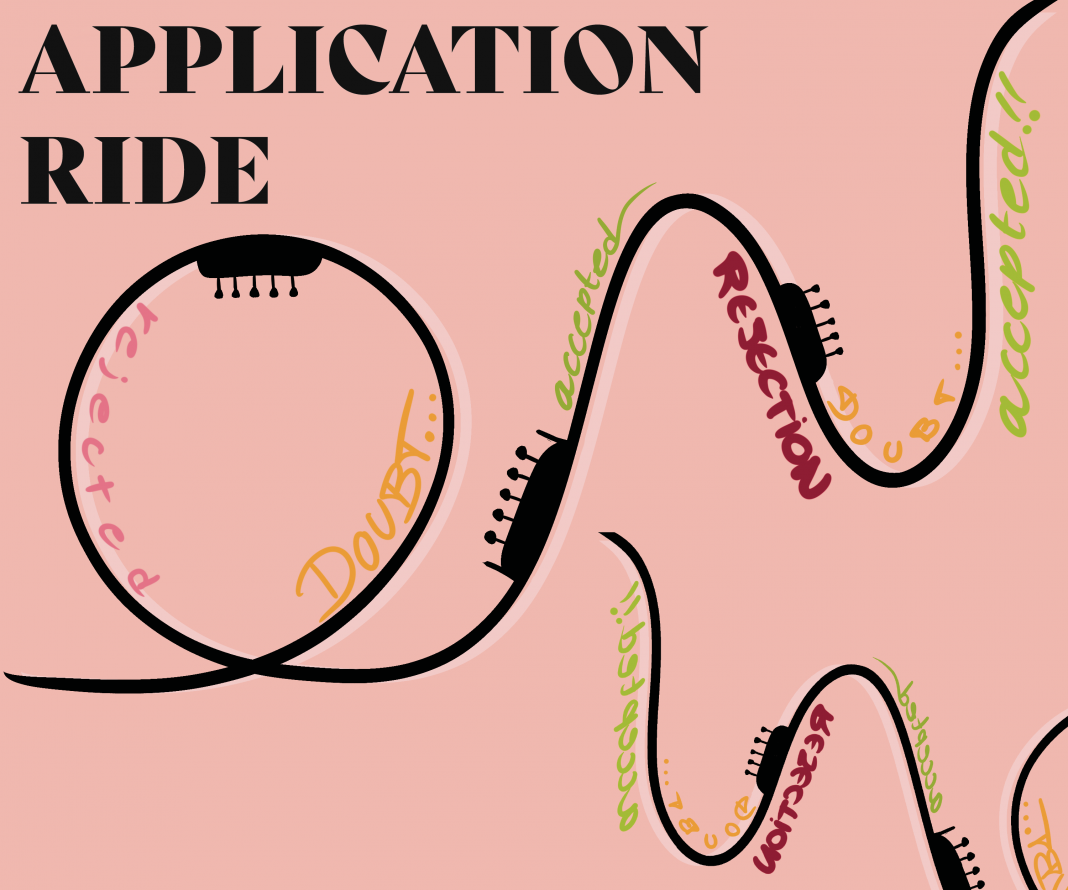

It’s a cyclical issue. When colleges receive too many applicants, they must become more selective with the students they accept. This in turn causes students to apply to a higher number of colleges to offset the risk of getting rejected.

We’ve normalized applying to schools offhandedly, and in doing so are losing sight of what is truly important about college. Tsai’s choice to apply to each of the top 10 universities in the country — all wildly different schools in terms of location, culture and opportunity — evokes the sense that the name attached to a college education is more important than the college itself. Due to this fact, the choice to apply to every top school is only smart in a gambling sense. The more schools they apply to, the higher their odds are of being selected. In Tsai’s case, despite several schools rejecting or waitlisting him, he ended up getting into multiple top schools through this strategy.

Tsai is clearly not the only student using this method, as applicant numbers are increasing across the board. If the end goal is to go to a top school regardless of its other aspects, then the ‘apply everywhere’ method works. This strategy has slowly trickled down to schools in the top 30-50 range nationally, as shown by UM’s recent increase in selectivity.

But prestigious colleges also come with prestigious prices, as seen with application fees. Non-refundable and mandatory, application fees are generally used to cover application processing and weed out applicants who aren’t as serious about attending. Depending on the school, fees can range from $50 – $100 for just one application. Top universities like Stanford, Cornell and Yale all boast application fees upwards of $80. With this in mind, the ‘apply everywhere’ strategy favors affluent individuals who can afford to spend thousands of dollars on application fees. It isn’t financially feasible for economically disadvantaged students to apply to 10+ schools, especially when SAT and ACT fees and college tuition are accounted for.

The true problem is that the process of getting into a top university is flawed and steps could be taken correct this behavior.

A limit on the amount of schools a student can apply to is conceivable. It would take large changes to the infrastructure of the admissions process, but would benefit students, as they would have to more carefully consider if applying exclusively to top universities is worth the risk. Additionally, students would have to narrow down the top schools to their favorites and they would be far more likely to apply to schools that resonate with their values.

College is a tried and true road to success and one should grant empathy to students who desperately want to attend a prestigious university for the sake of its name brand. Although it does grant security, a prestigious school is just one road to success and incentivizing other forms of success would definitely ease the incredible mental health burden today’s college students face.

A forceful change would be far more effective than attempting to coax students to think differently. If students are encouraged to approach the college admissions puzzle from a more personal, less societal angle, then the U.S. could see a nuanced problem effectively mitigated.

Jayden Cohen is a freshman majoring in Business Analytics in the Miami Herbert Business School.

Correction: An earlier version of this story published on Oct. 5 incorrectly described the role that College Board plays in the college admissions process. This statement was revised on Dec. 6.