This story was written by reporters working for CommunityWire.Miami, the University of Miami’s only graduate-student publication.

From a small Black resort hotel in Miami, Cassius Clay took his first steps to a new boxing title and a new name.

The then 22-year-old Clay was staying at the Hampton House Motel in the segregated Brownsville community when he captured the heavy-weight championship title from Sonny Liston on Feb. 25, 1964, at the Miami Beach Convention Hall.

Clay returned to the Hampton House to celebrate his success. Invited to the party were singer-songwriter Sam Cooke, NFL star Jim Brown and Malcolm X, the Nation of Islam leader credited with Clay’s religious conversion to Islam and his Muslim name, Muhammad Ali.

Now, 58 years later, the renovated and renamed hotel is revisiting that heady time when Ali bragged and boxed his way onto the world stage.

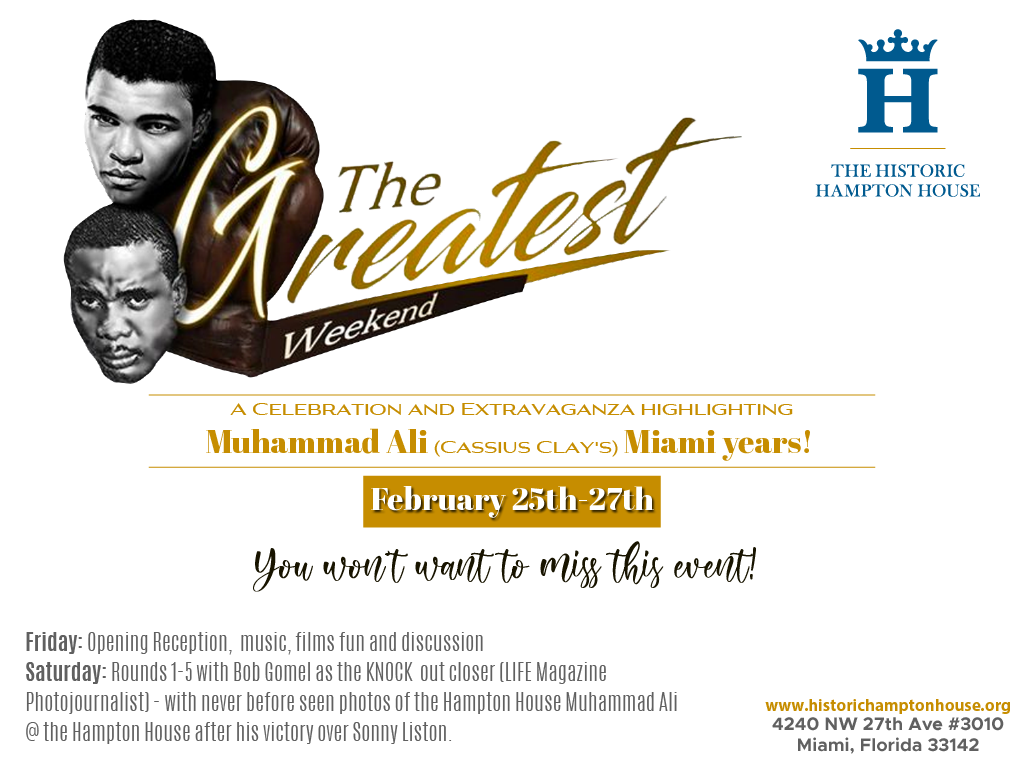

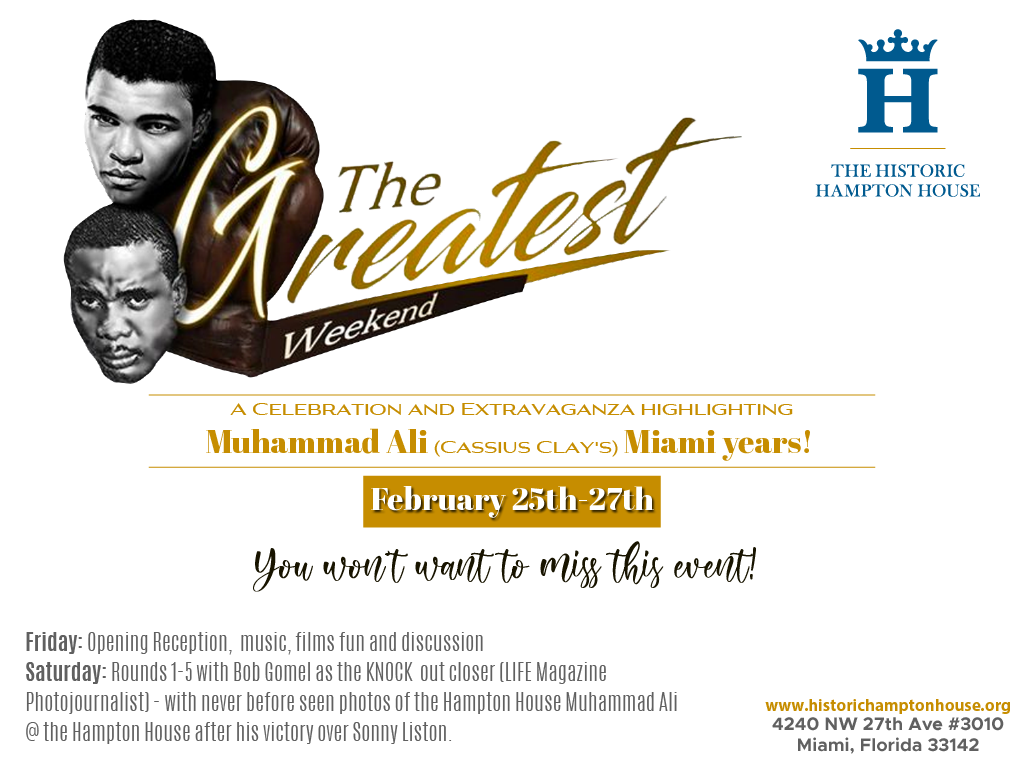

The Historic Hampton House will host “The Greatest Weekend,” Feb. 25-27, with films, entertainment and guest speakers who will reminisce about the boxer, his challenges and achievements.

“We are bringing back that great weekend, reliving the fight and all the wonderful things that took place at the time,” said Jacquetta B. Colyer, board chair of the Historic Hampton House.

The 1964 victory party is the focus of Regina King’s 2020 film, “One Night in Miami.” While the movie’s rendition of what was said among the Black celebrities may be imagined, the actual victory party at the Hampton House was real, Colyer said.

“Ali had a suite at the Hampton House, and he came right back here to celebrate his victory,” Colyer said. “They had planned to celebrate at the nearby Fontainebleau Hotel on Miami Beach, but Ali could not receive accommodation there. He could win the heavy-weight championship of the world but not sleep at the Fontainebleau.”

The “Greatest Weekend,” while offering reflections on the fight and Ali’s surprise win over Liston, will highlight Ali’s Miami years and the role the Hampton House played in incubating Ali’s rise to heavy weight boxing champion.

The event is also one of the ways the Hampton House board is trying to revive the hotel’s presence and relevance in the community.

Opened in 1953, the Hampton House Motel catered to the Black middle class and attracted celebrities in entertainment, sports, business and civil rights at a time when segregation kept Blacks from staying at establishments for white guests.

The motel was one of 1,100 “Green Book” hotels across the country that offered Black travelers accommodations during segregation. Victor Green’s book included several Florida safe havens. Now only seven hotels, including the Hampton House, have survived, Colyer said.

For a moment, it seemed the Hampton House was destined to close its doors as well.

Following the Civil Rights Movement, Blacks began to stay at previously white-only establishments, and the Hampton House and other “Green Book” hotels began to close. The motel fell into disrepair and was scheduled for demolition in the 1970s until retired social worker and educator Enid Pinkney devoted her life to restoring it.

“The young people need to know the history of our community and they don’t get it in school because the teachers don’t know it,” said Pinkney, who was determined to renovate the community eyesore.

Following years of fundraising and a two-year construction project, the hotel’s main floor was brought back to life and reopened for special events in 2017. Additionally, two boutique historic rooms, the Martin Luther King Jr. room and the Cassius Clay room, were fully redone.

What has already been restored cost $7 million, funded in part by Miami-Dade County through the general obligation bond program and various fundraisers since 2001. The total restoration of the 30,000 sq. ft. building will cost $15 million, Colyer said.

But as board members brainstormed ways to restore more rooms and create a safe space for younger generations interested in learning about Black culture and history, COVID-19 put the plans on hold.

“All of the human foot traffic came to a halt during 2020, but the bills kept coming,” Colyer said.

Although the COVID-19 shut down wasn’t good for business or the board’s goals, it did give board members time to reflect.

“It gave us a chance to really look at who we are and what we really wanted to do,” Colyer said.

Now, they hope to get The Historic Hampton House rebuilt, up and running, and fully functioning.

“We want the hotel to be what it was, you know, a hotel,” Coyler said.

The plans meet Willie Oliver’s approval. He used to pass by the hotel without giving it a second notice.

“I would ride by and not think anything of it, but now I walk by and some of the people that walked into this building makes me honored to be in this place,” said Oliver, 66. Both he and his wife recently volunteered at Pinkney’s 90th birthday celebration at the hotel.

Janiece Smith, 44, was also a volunteer.

“I remember the first time I walked through the doors and felt the Hampton House,” Smith said. “I could actually feel like heavy footsteps of the giants that walked these halls. People that made such an impact in the life that I lived today. It is an honor and a privilege to keep this legacy going.”

A Feb. 25 reception kicked off “The Greatest Weekend” events, which are free and open to the public through Feb. 27. For the event schedule and to register, visit Eventbrite.

For more information about the Historic Hampton House, check out their website.