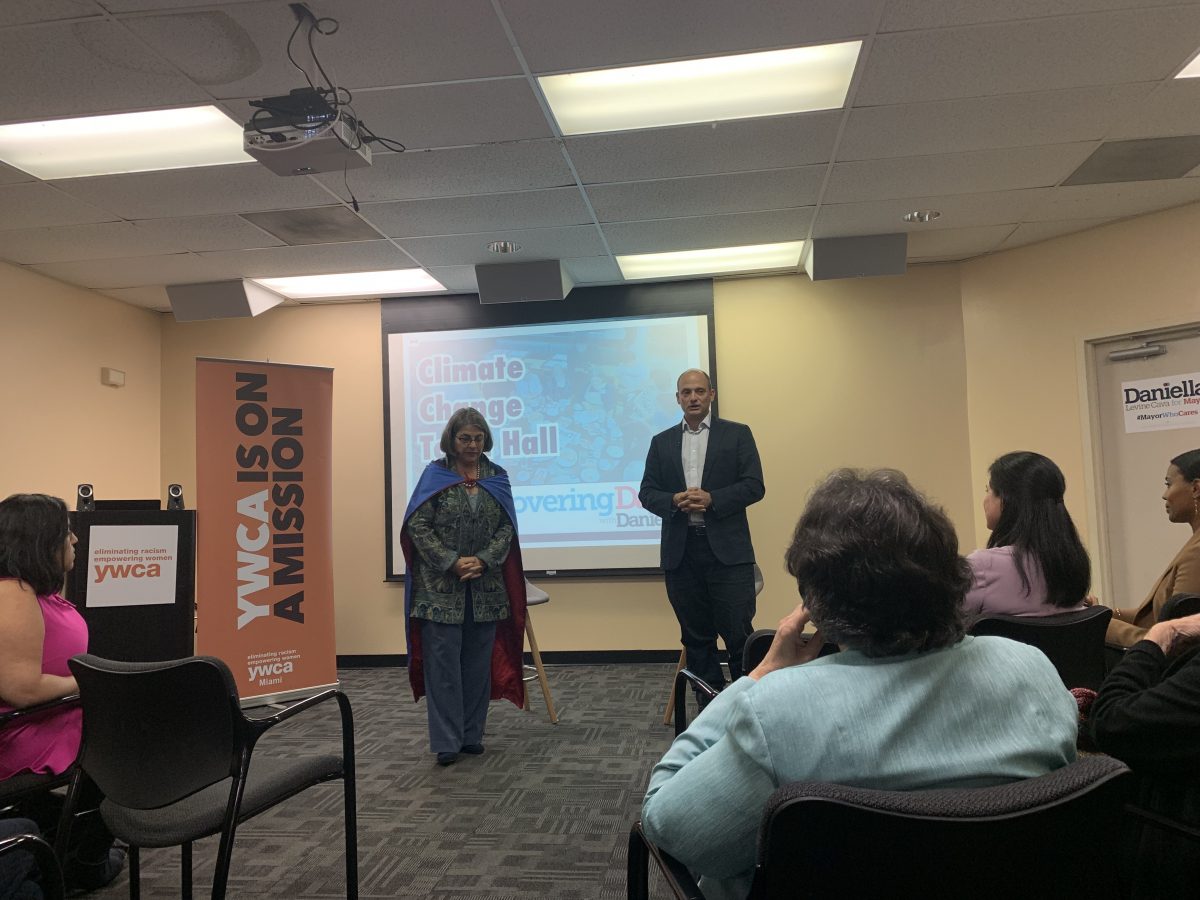

Monday, Nov. 18, County Commissioner Daniella Levine Cava and Sen. Jose Javier Rodriguez led a discussion on the climate change crisis impacting South Florida. The event came just two months after Miami-Dade’s youth assembled at City Hall to protest the inaction of Floridian politicians in addressing climate change.

Community members gathered at the YMCA in Overtown to hear the future plans of their elected officials as well as voice their own concerns as constituents.

“Climate change is an existential threat, [and] I don’t see the political will from our leaders,” said Gilbert Placeres, an attendee and active member of Engage Miami, an organization that empowers youth in Miami to vote.

It was just this sentiment that Levine Cava and Rodriguez sought to address.

“This is the critical issue of our time. It is truly an existential threat, and we need to address this boldly, and we need to act now,” said Commissioner Cava.

The commissioner went on to discuss a lengthy track record of legislation passed under her administration to combat the climate crisis and its impacts. The Miami-Dade County Commission has worked to deter chemical dumping in water streams, abolish styrofoam in parks, open recycling opportunities at docks and ban fracking in the county.

Yet, both the audience and leading politicians acknowledged that this wasn’t enough.

“Why aren’t we the leaders in the green economy? Why aren’t we at the forefront of solar?” asked the commissioner. While states such as Texas are at 20 percent renewable energy, Florida, the “sunshine state,” lags behind at 3 percent.

This past August, Rodriguez and Orlando Representative Anna Eskamani refiled a previously rejected bill that would set a state goal to reach 100 percent renewable energy by 2050. The bill will be voted on by the Florida Legislature this coming January.

Such movement toward a statewide green transformation could also have much larger implications.

A “green job” refers to any occupation in a sector that promotes sustainability and environmental restoration, such as energy consulting or water quality management. In theory, the creation of such jobs could bolster the economy, boost the income and living-quality of Miami-Dade residents and tackle climate change in one sweep.

The senator also discussed two upcoming bills that would propel Florida into climate change action at the state level. The first involves the creation of a sea-level impact projection program, while the other requires a health climate impact study to be conducted annually.

“In my view, the way that most Miami-Dade residents will [face] a real impact and encounter with climate is not going to be with a sea-wall, it’s not going to be their property value, it’s going to be their health,” Rodriguez stated.

Both politicians were also quick to recognize the inequity that could breed in the aftermath of climate change. Overtown’s own experience with climate gentrification and the vulnerability of Miami-Dade’s populations that cannot afford to move in the case of natural disasters suggest the dangers of lacking sea-level rise infrastructure and a climate change mitigation plan, they said.

“The folks that are most likely to be engaged [and] most likely to vote are more likely to have more money, be white, and not face the problems most of the time, so it’s more important for the politicians to listen to the community that’s directly facing the problems,” said Placeres.