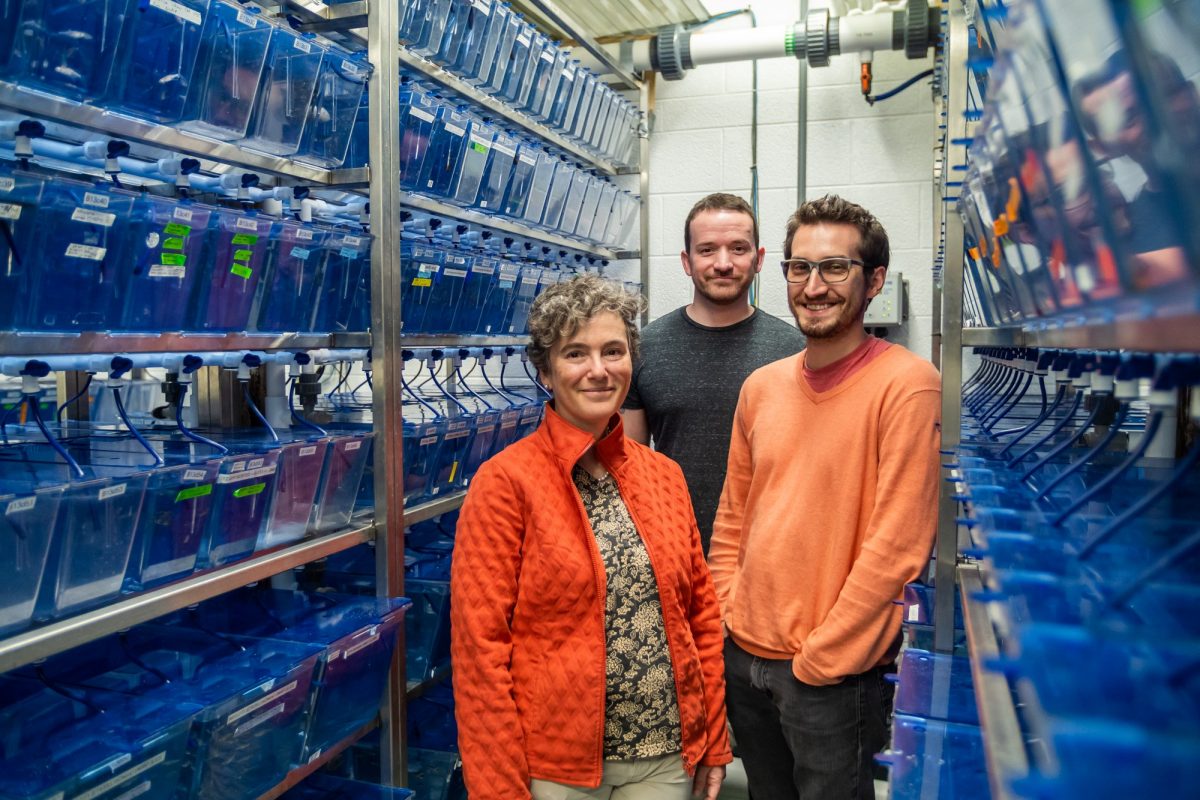

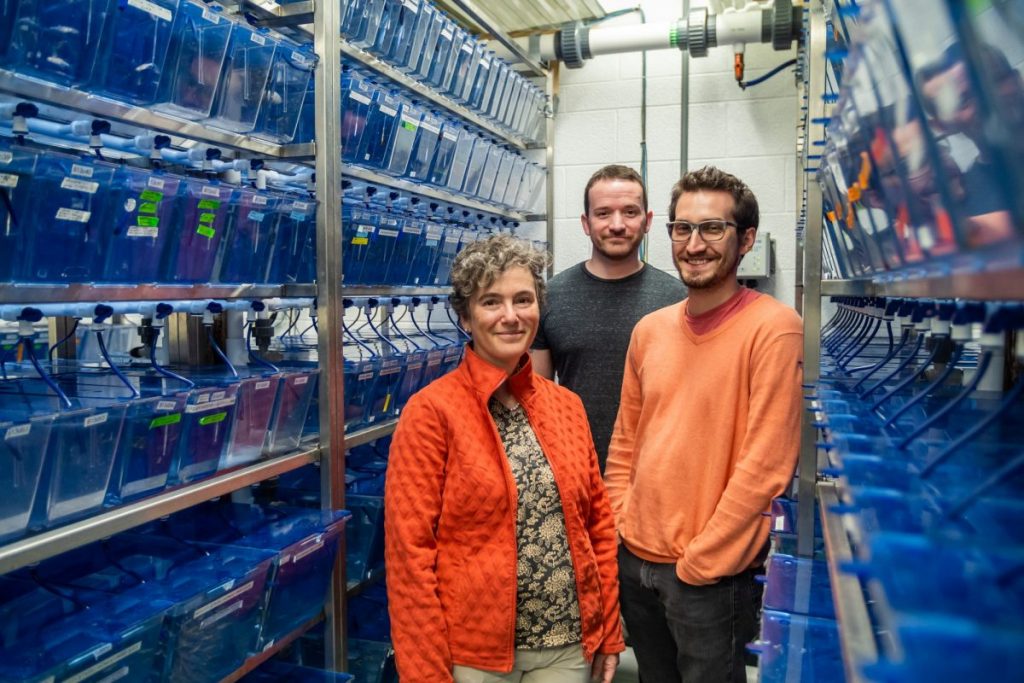

For the past nine years, a zebrafish research facility has been fully operating under students’ feet at the University of Miami. The Cox Science Building not only provides classroom and lab space for university students but also houses schools of small, striped fish that are becoming increasingly more important in the scientific community. Cox has kept the Zebrafish Core Facility hidden from visitors while inconspicuously conducting unique investigations that have assisted in unveiling secrets of the human body.

According to associate professor in the department of biology Julia Dallman, zebrafish research has been going on since the 1980s and has provided researchers with a revolutionary approach to the observation of genetic and disease-related human traits.

Researchers at UM are currently investigating how the SHANK3 gene, which is linked to autism in humans, could be affecting the digestive functions of the fish. Through this, they hope to gain insight into how disruptive genes linked to autism manifest themselves in altered gut functions within forming embryos.

In the early stages of zebrafish development, the embryos are transparent, which allows scientists to observe the effects certain conditions can have on embryos.

The zebrafish facility has an independent air conditioning unit, osmosis water system for the tanks and a supply of live micro-shrimp used to feed the zebrafish. Dallman was tasked, along with another professor, to create the facility in 2007 which then came to fruition in 2010. She has had experience working with zebrafish in the lab since her time as a graduate student at the University of Washington.

The facility does not conduct research itself but instead provides UM and South Florida researchers with zebrafish embryos, larvae and adult zebrafish for investigative and teaching purposes.

Senior Evan Sarmiento has worked with zebrafish since his freshman year. His responsibilities include preparing the chemicals and supplies for science classes that incorporate zebrafish into their curriculum for educational purposes.

“By the end of the semester, Mrs. Linda White (a UM research associate) told me about an opportunity in the zebrafish facility,” said Sarmiento, a double major in biology and Spanish. “They were looking to feed the fish. I was able to clean the tank and learn what these fish are used for.”

Freshman Cameron Herter said he believes that zebrafish research provides an incredible opportunity for discoveries to be made in the field.

“Zebrafish, as a model organism, allows the scientific community to explore the uniqueness of marine model organisms compared to their terrestrial counterparts,” said Herter, a neuroscience major.

Despite the advancements and benefits that come with the embryo research, there are ethical questions raised as to how the work is conducted. To conduct embryonic research, the Zebrafish Core Lab must often kill zebrafish fetuses. Dallman stated that the manner in which they put down the test subjects is humane and moral.

“Now sometimes we stay in the nervous system and that is when we have to kill the embryos,” said Dallman. “We make it so that they are anesthetized before ending their lives to do the staining of the nervous system.”

Even though the facility does kill some embryos, a female zebrafish can lay up to 50 to 300 eggs per week. With a life span of eight years, a zebrafish can produce a significant amount of offspring in its lifetime.

Animal experimentation has been up for debate for years, and the scientific community has made distinctions based on the contributions the research provides to society. Herter concurs, saying that this has been a topic of discussion in many of his science classes.

Dallman said that they do not raise all of the offspring, but they make sure that the ones who do are raised ethically. This includes keeping fish together in order to allow them to be social, feeding them live food twice a day and removing and treating any sick fish from the school.

“At the end of the day, to gain information that will help millions of humans that are dying from diseases— the scientific community decided it was okay to experiment on animals in certain situations,” said Herter. “In a sense, they do not do it to harm the animals but to benefit the whole society.”