The shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas has sparked the same predictable conversation about gun control and mental health that we rehash after every mass shooting, in which the perpetrator is a white (or white-passing) American male. Rarely addressed, however, is the way we’ve chosen to frame the issues of violence and mental health as inextricably linked.

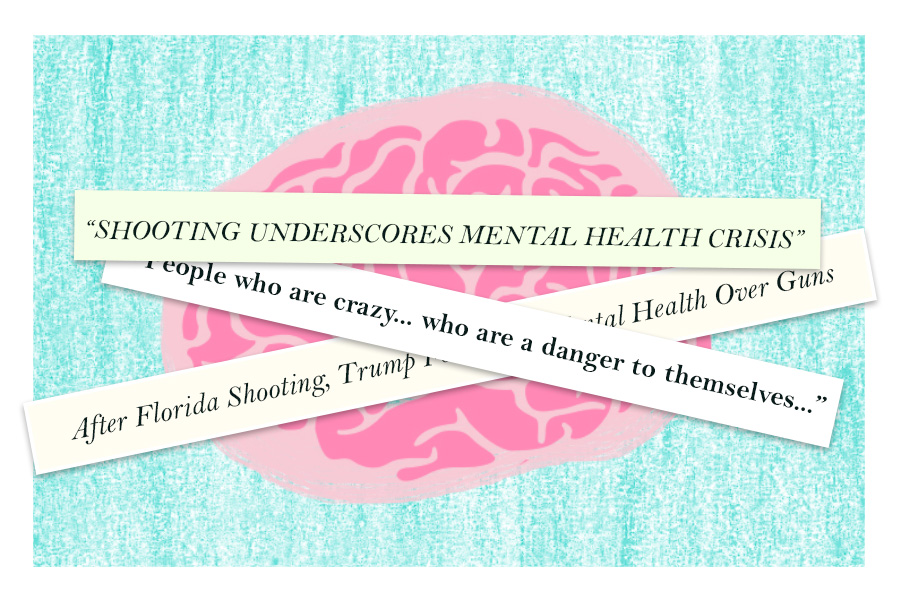

Although opinions vary on what should be done about gun control, there seems to be one overarching fact that people on both sides of the argument agree on: “The mentally ill” should not have access to weapons. To soften the way that sounds, we also like to float the ideas of addressing mental health issues in students or making counseling more accessible to those who need it. It’s not a coincidence that the only time we collectively tackle mental health is right after a mass shooting.

Ableism, or the devaluation of people with disabilities, is as rampant in our society as every other -ism yet receives little attention.

Given this ableist backdrop, we can all comfortably simplify the issue and blame the actions of one deranged mass shooter on “poor mental health,” citing his “traumatic” upbringing as an obvious precursor to his actions.

Also alarming is the fact that the topic of mental health is appropriated by groups such as the National Rifle Association and used as a shield to avoid having real conversations about gun control reform. At the CNN Town Hall held on Feb. 21, NRA spokesperson Dana Loesch said “none of us support people who are crazy, who are a danger to themselves, who are a danger to others, getting their hands on a firearm.”

This statement makes the faulty assumption that “crazy people” (read: those living with mental health issues) are always a danger to themselves or others. Loesch also failed to acknowledge the highly subjective and variable nature of psychiatric diagnoses.

In reality, people with mental health disorders are “10 times more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators,” according to the Mental Health Foundation. Only 3 to 5 percent of violent acts are committed by people with severe mental health issues, according to Scientific American.

While the Parkland shooter did have depression, ADHD and autism, these diagnoses alone cannot explain his behavior.

These issues are often thought of as shameful and embarrassing already, and when someone acts out irrationally or violently, we dismiss them as “crazy.” The ableist stigma that makes so many of us automatically associate the shooter with mental instability or illness is the same stigma that holds individuals back from seeking help when their health is at stake.

Perhaps we’re just desperate to understand why people carry out these unimaginable acts of violence. Mass killings are highly gendered crimes, with males making up 98 percent of the murderers. Furthermore, gun control group Everytown for Gun Safety analyzed FBI data on mass shootings from 2009 to 2015 and found that “57 percent of cases included a spouse, former spouse or other family member among the victims – and 16 percent of the attackers had previously been charged with domestic violence.”

In light of this evidence, it becomes clear that mass violence can be caused by things other than mental illness, and that the contributing factors are extremely complex.

While mental illness is an easy target, perhaps toxic gender expectations are (at least partially) to blame. The quiet loner that you think is “mentally disturbed” is probably not as likely to carry out a mass shooting as much as the guy who abuses his girlfriend.

If we care about mental health as much as we claim to in the aftermath of a shooting, we need to stop antagonizing this community by making irresponsible blanket statements that equate mental health issues with violent behavior.

Alexandra Diaz is a junior majoring in political science and women’s and gender studies.