While young people are most aware of the events in Ferguson, Mo. and protests of cases since then, Miami residents revisit the racial tensions and chaos caused by the destructive McDuffie riots in the 1980s.

At the University of Miami, several groups have tried to raise awareness for racial issues in the wake of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, which gained visibility in 2013 after the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the death of Trayvon Martin.

The movement has been on the forefront of giving national attention to many cases of black deaths in law enforcement encounters, including Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Freddie Gray, Eric Garner, Sandra Bland, among others. More recently, questions have been raised about the police account of the death of 15-year-old Jayson Negron, who was shot after a brief police chase involving a stolen car.

Since its conception, the BLM movement has sparked debate and intense disagreement, including on UM’s campus. Some view BLM as a movement that undermines the police force, while others see it as shedding light on race relations in America.

In 2016, David Ikard, director of Africana Studies at UM, taught a two-semester undergraduate course to educate students about the BLM movement and its principles.

“We want serious conversations about improving race relations,” Ikard said. “There has to be a serious overhaul of the policing and judicial system to correct the whole culture of policing.”

A second BLM course taught by Professor Osamudia James, vice dean of the UM School of Law, began on March 9 and was open to all students and faculty.

James created the course in hopes of furthering a conversation “that is long overdue,” according to an interview with James from a previous article from The Miami Hurricane.

On March 2, junior Jackson Stewart was caught on video surveillance cameras stealing a banner featuring the words “Black Lives Matter” and silhouettes of individuals.

The banner had been purchased by the Yellow Rose Society for Black Awareness Month in February to display in the UC Breezeway. Twenty days later, Stewart admitted to taking down the banner, saying he had been “embarrassed” by it, according to police reports.

Rebecca Garcia, a senior majoring in International Studies, is a former member of the university’s Standing Committee on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, and the Task Force for Addressing Black Students’ Concerns.

“How is it possible that still, in 2017, one student can mindlessly deny another student’s right to assert the legitimacy of her own race in a pacific, non-combative manner?” Garcia said of the BLM banner theft in an email interview. “Incidents like these only prove to me that there is much work to be done.”

Braylond Howard, a rising senior and president of United Black Students, played an active role in the creation of initiatives set forth by UM President Julio Frenk aimed at “building a culture of belonging,” as Frenk described in a 2015 letter.

However, Howard, who served as a member of the original task force commissioned by President Donna Shalala, said he believes that very few of the initiatives have been accomplished. He expressed concerns about the inevitable graduations of the “original thought-leaders” of the initiatives and worried that newer students would have no direction to follow. The initiatives included the exploration of diversity programming, the enhancement of sensitivity training, and the exploration of current efforts in the recruitment of faculty.

“I worry for the future of these [initiatives] coming into action,” Howard said in an email interview. “I do not think the school is doing enough.”

Campus-wide debates on racial issues intensified as a result of high-profile police shootings. Most visible was the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, which led to a number of protests on campuses around the country, including one at the University of Miami in December 2014.

“Violence and excessive use of force do not need to be utilized in every interaction between the police and the community,” Garcia said. “The police have a duty to protect, but they must do so without infringing upon basic human rights.”

Many UM students took to social media in response to the on-campus march and an email sent out by then President Donna E. Shalala in which she encouraged students to engage in “respectful dialogue.” The administration’s approach to the issue has since received some criticism.

“The system the administration has utilized to address racial inequities depends far too much on bureaucracy, and not enough on addressing the reality of race relations on campus,” Garcia said.

Ferguson was just the beginning of the public outcry. It would be followed as more cases gained national attention: Tamir Rice, Freddie Gray, Eric Garner, Sandra Bland, among others.

While the rest of the world was watching, the Ferguson case evoked memories among Miami residents of the McDuffie case from thirty-seven years ago that would forever alter the city’s history.

The day of the verdict

On this day 37 years ago, a not-guilty verdict was reached on the manslaughter trial of four Miami-Dade police officers who were accused of police brutality and fabrication of evidence in the death of former Marine Arthur McDuffie.

On December 17, 1979, 33-year-old McDuffie suffered critical injuries at the hands of the four officers following a high-speed chase in North Miami, where the African-American community responded with anger after news had come out that McDuffie was beaten into a coma. He died four days later with multiple skull fractures.

At the time of the verdict, a young William Clark served as a head football coach at American High School in Hialeah. Tensions across the city were high, and Clark anticipated strong reactions in various communities if the officers were acquitted.

On that morning, May 17, 1980, a Tampa jury found the four officers not guilty, prompting immediate reactions in the predominantly black neighborhoods of Liberty City, Brownsville, and Overtown. The subsequent unrest was televised for the world to see. Images of a protest in front of the courthouse where the officers were acquitted were broadcast, immediately followed by reports that an unruly crowd had gathered on 62nd Street and NW 15th avenue, in Liberty City.

“As I continue to watch the coverage, it became apparent that something was getting ready to pop off,” Clark said.

Clark’s first instinct was to pick up an aunt who lived in the area, where a large protest had escalated into a riot. Clark described how he witnessed agitators throwing rocks at a vehicle in front of him while he was waiting in traffic. The driver and passenger, both of whom were white, were pulled out of the car.

“I believe they were among the first casualties of the riots,” Clark said.

The next three days were plagued with widespread violence that resulted in the deaths of 18 people and $100 million in property damage. Businesses in the neighborhoods of Overtown, Liberty City, and Brownsville were looted and destroyed, including the Norton Tire Company warehouse in Brownsville. Since the 1960s and 70s, the building was seen by some residents as a symbol of brutality due to stories of black residents getting beaten and interrogated by police officers inside the warehouse, according to a 2015 Miami Herald interview with the warehouse’s owner.

“There was no longer any trust in the justice system, the police and city and county officials,” Clark said. “The realization that no one cared us about became very obvious.”

Many of the businesses that were razed during the riots were never rebuilt, including numerous grocery stores and a shopping center, leaving a deep, physical scar in the affected neighborhoods that continues to exist to this very day. In Brownsville, while new businesses have sprung up, including a Checker’s, the neighborhood continues to endure severe economic issues, with 43% of its residents living in poverty as of 2014, according a 2015 report by the Metropolitan Center at Florida International University.

“Black Miami never recovered after the riots,” Clark said. “Many of us continue to work on the recovery as we speak.”

Policing in a Troubled Atmosphere

1980 proved to be a tumultuous and violent year for the city of Miami, plagued with a record 537 murders and numerous turf wars with gangs and drug cartels. The previous year, 1979, was marred with numerous police brutality cases, including the sexual abuse of an 11 year-old black girl by a white state trooper who later received three years’ probation, that provoked outrage and led to an era of mistrust that reached its peak when Arthur McDuffie was killed.

At the time of the verdict in the McDuffie case, a young David Rivero was in the process of becoming a police officer after studying criminal justice at FIU. Today, he serves as the chief of the University of Miami Police Department (UMPD).

Rivero grew up in the neighborhood of Edgewater, just east of Biscayne Boulevard. In 1980, he worked as a mechanic at Sheehan Buick on SW 8th street. He recalls “seeing the city burn” on May 17.

“I remember driving and seeing all the fires billowing up smoke just west of our home,” Rivero said. “We watched the verdict on TV and the subsequent news coverage of the violence as it started to develop.”

He noted, however, that the unrest had no impact on his decision to become a police officer.

“It scared me a little bit, but I knew that that was my calling,” he said. Several years before the riots, before he knew he wanted to become a police officer, Rivero was accepted to Washington University in St. Louis to study on the pre-med track.

After a somewhat disappointing year in St. Louis, Rivero returned to Miami for the summer, during which he got the opportunity to ride with a police officer who was dating his sister at the time.

“For me that was it,” Rivero said. “I fell in love with it. This is what I wanted to do.”

Throughout his thirty-seven years as a police officer, Rivero served as a detective, sergeant, lieutenant, captain, commander and major at the Miami-Dade Police Department. By the time he became the UMPD Chief in 2006, Rivero possessed a tremendous breadth of experience with multiple city and federal honors, including letters of commendation for meritorious service from the FBI and the Miami Dade Police Department. He expressed a desire to build a better investigative unit at UM than the one that existed then.

“I’ve been involved in investigations my whole career,” Rivero said. “It’s the thing that I love the most.”

Bearing the responsibility of leading a police force tasked with protecting tens of thousands of students and faculty members, Rivero emphasizes the need for community policing and establishing dialogue with everyday citizens, often times advising fellow officers to go out and speak to local residents.

Erick Gavin, president of the UM Black Law Students Association reflected on his “scarce” interactions with the University of Miami Police Department.

“The one positive thing I can say is that they seem to be trying to engage with the students to do a better job beyond what is normally expected of police officers,” Gavin said in a phone interview.

According to Rivero, UMPD has prided itself on investigating every single crime.

“We’re setting a record this year for the lowest crime rate ever at UM,” Rivero said.

Over the years, the number of reported incidents at University of Miami has decreased consistently, from 454 in 2003 to 179 in the 2014-2015 academic year.

“My belief is that it’s better to prevent a crime than catch a criminal committing a crime,” Rivero said.

John Gulla, an emergency management coordinator at UM, has expressed his respect for Rivero, having worked with him for nine years at UMPD.

“Chief Rivero guides UMPD toward a comprehensive approach to campus safety, including not only the presence of well-trained and experienced patrol officers out on the road every single day, but a robust community-policing effort that includes daily communications with administrators, departments, students and staff,” Gulla said in an email.

Consequently, in light of recent police shootings and episodes of unrest across the country that often bear resemblance to the events of 1980, Rivero bemoans what appears to be a tenuous relationship between African-Americans and other minority communities, and law enforcement officials.

“I think the hardest thing about policing now is that people used to believe a cop’s word 100% of the time, and now folks don’t believe it,” Rivero said. “A cop’s word is not worth as much as it used to be. That’s what hurts me. It hurts my profession. It hurts my officers. It’s because of these few cops that have lied, that have tried to cover things up, that have done bad things in policing that has caused us to be in the situation that we are now.”

The Ongoing Debate

Since 1980, the black community of Miami-Dade County has made modest improvements in some areas of racial disparity, but continues to struggle in other areas, according to reports from the Department of Regulatory & Economic Resources and the Metropolitan Center at Florida International University.

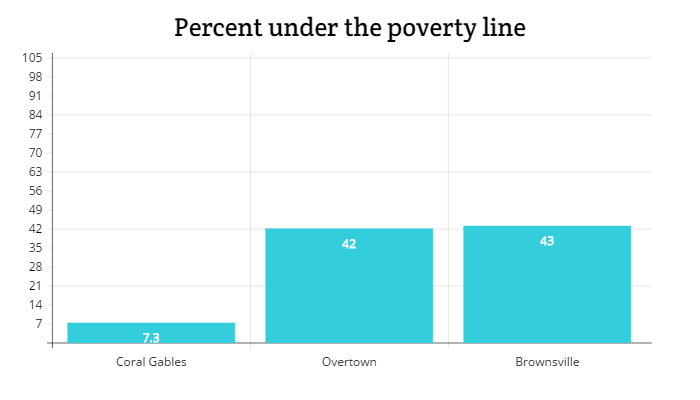

There are sharp socioeconomic differences between Coral Gables, which has a 7.3% poverty rate according to Census data, and the neighborhoods of Overtown and Brownsville, which have poverty rates of 42% and 43%, respectively.

Gavin spoke about a perceived disconnect that exists between UM students and the residents of these poor neighborhoods.

“I think there’s more desire among students to get involved because of the things they might be hearing about,” Gavin said in reference to racial disparity. “But I also feel that the disconnect is still very, very startling.”

According to students like Gavin, there’s no clear-cut answer as to how to confront police brutality.

“That’s a very complex and difficult question,” Gavin said. “You have to start answering, ‘How do we make sure that the police actually are able to do their job but at the same time are not doing their job to the extent in which it’s detrimental to the people?’”

It is a question that is debated among many students at UM, including students that aren’t members of activist groups or political organizations on campus.

Andre Rivero-Guevara, a junior majoring in applied physics and the president-elect of the Society of Physics Students, attributed the ongoing racial disparity to gang violence and the “oversight” of impoverished neighborhoods by law enforcement.

“Such oversight allows this festering culture of ignorance,” Rivero-Guevara said. “The success that these gangs and these individuals whose motives are to steal and to violate is so clear that they can continue professing this way of life, making it genuinely hard for those who want to get out of such communities to get an education and to even see how the education can help their community.”

Violent crime rates are highest in the neighborhoods of Opa-Locka, Overtown, and Liberty City, according to a 2016 annual scorecard from the Metropolitan Center at FIU. In Overtown alone, the crime rate is 30.15 per 1,000 population. In comparison to Miami-Dade County’s crime rate of 10.45 per 1,000 population. The scorecard attributes the high violent crime rates in these neighborhoods to “crossover effects of economic disparity, high poverty levels and low educational attainment.”

According to UMPD Chief Rivero, students who disagree with each other on racial issues should remind themselves that they are all “Americans, Floridians, and Miamians” and that they should not divide themselves along racial or ethnic lines.

“Until we can all say we are all proud Americans and we continue to splinter ourselves into all these little groups, we’re going to have clashes between those groups,” Rivero said. “I don’t know what the solution is, but the one thing to learn from the 1980 riots is that African-Americans are – whether it’s true or not – they feel they’re mistreated and we need to acknowledge that. We need to say to ourselves, ‘What can we do to improve that?’”

After noting that UMPD’s attempts of engaging with students was the one positive thing he could say about the department, Gavin went on to explain how UMPD could potentially serve as a model to other police departments, saying that a “more complex approach” based on connection would be “mutually beneficial” for police officers and members of the community. However, Gavin noted that other police departments would have their own challenges.

“It is easier [for UMPD] because the University of Miami does not have a lot high level policing to do,” Gavin said.

Going forward, as the university continues to try to raise awareness of racial issues by starting cultural competency training sessions in Fall 2017, UMPD Chief Rivero says that he will continue “forcing” his officers to interact with members of the community in hopes of bringing about “friendly encounters.”

“That’s how we build better relationships with our folks,” Rivero said. “We need to do a lot more of that.”