Continual incidents of “fake news” – the deliberate publishing of misinformation purporting to be real news for profit or out of malice – have led to rising tensions between the mainstream media and President Donald Trump’s administration, tensions that have negatively impacted the public’s trust in the journalism industry many University of Miami students will be entering post-graduation.

The spread of this “fake news” has also caused students to question the basics of journalism and its influence over public opinion.

A study conducted by Stanford University earlier this month found that although social media wasn’t the main source of political news for most Americans in 2016, 14 percent said they relied on Facebook and other social media sites as their most important source of election coverage.

With election topics generating high amounts of traffic on social media, it was easy for fake news to be hidden among links, spreading inaccurate news intended to potentially sway someone’s opinion to vote for another candidate.

“Voting is one of the most sacred privileges we enjoy as citizens, and every voter has the right to accurate information about the candidate they’re voting for,” said senior Oliver Redsten, station manager for University of Miami Television (UMTV).

Another issue Redsten has noticed is the dissemination of false statements said on live television.

“In the era of 24-hour cable news we’re living in, it’s increasingly common to see political pundits making ridiculous claims on national television,” Redsten said in a message. “It’s incumbent on the broadcast journalists who are conducting the interviews to correct any false claims that are made on the airwaves.”

There have been multiple instances of the Trump administration making false claims throughout its first weeks in office. However, one of the most controversial statements came a few hours after Trump’s inauguration, when White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer said during the first press briefing that the crowd at the event was the “largest audience to ever witness an inauguration, period,” an assertion widely discredited by journalists.

Former President Barack Obama’s 2009 inauguration ceremony set the record for crowd size, with an estimated 1.8 million people in attendance.

“What the media reports by using photos, interviews, experts, studies and other journalistic skills are facts,” said Heidi Carr, professor of media relations at the School of Communication.

Redsten used the Jan. 22 interview NBC journalist Chuck Todd conducted with Counselor to the President Kellyanne Conway on “Meet the Press” as an example of correcting false claims. During the interview, Conway used the phrase “alternative facts” to defend the factually incorrect statements Spicer made on the size of Trump’s inauguration crowd.

“You’re saying it’s falsehoods,” Conway told Todd. “Our press secretary gave alternative facts.”

Following her defense, Todd immediately corrected her on live television. Redsten said Todd’s response was exemplary.

“But inevitably, there will be false claims that go uncorrected, and it’s absolutely essential for every citizen to have healthy skepticism about the information they’re receiving,” Redsten said.

“THE OPPOSITION PARTY”

Among those accusing journalists and media networks of being corrupt and dishonest is Stephen Bannon, Trump’s chief strategist.

“The media here is the opposition party. They don’t understand this country. They still do not understand why Donald Trump is the President of the United States,” he said in an interview with The New York Times on Jan. 25.

Although Bannon negatively classified the media as an ‘opposition party,’ Carr said being an opposition party is what journalists should be.

“Journalists are always the ‘opposition party.’ They are not there to parrot the platform of the Republican or Democratic Party. They exist to question, to research, to get to the facts and put stories in context,” Carr wrote in a message.

Bannon’s statement and the general public’s trust in journalism – which is at an all-time low, according to polls – questions the role of journalism during a time when credibility has become indispensable in combatting the rise of “fake news” and the wide circulation of false statements.

During a Jan. 11 press conference, Trump called CNN “fake news” because of its decision to report on an unverified dossier from intelligence officials that had been circulating among journalists and had made its way to Obama and intelligence agencies. The dossier, which included notable errors, alleged Trump had been “cultivated” by the Russian government for years. Other publications like The Washington Post criticized the publication of the dossier on Buzzfeed, and even CNN acknowledged that the claims could not be independently corroborated.

NBC News correspondent and MSNBC’s host of Morning Joe, Willie Geist, said U.S. presidents describing media outlets as biased or untruthful is not new. However, Geist said, the difference between previous presidents and their cabinets was that they had these discussions “behind closed doors,” whereas Trump publicly “spins” the facts against the media. Despite the backlash, he said journalists must continue to do their jobs.

“I think as journalists, I’d be champing at the bit to get in the middle of this and be a fact finder, a truth teller, fact checker and somebody who can keep an administration in check,” Geist said in a phone interview.

As for the current state of journalism for graduating students, Redsten said the spread of these false stories will actually help journalism as an industry.

“It’s more important than ever to have principled, professional journalists who are committed to fairness and accuracy. It’s up to all of us as citizens to support the news outlets that are doing it the right way,” he said.

For Geist, who has had a career in journalism spanning 20 years, being called “biased” by the public comes with the territory because, he said, people either don’t believe in the way the facts are presented or they think other topics are more important to discuss. Regardless of public opinion, journalists have a duty to strive for fair reporting.

“I’ve always thought objectivity is sort of impossible because we’re human beings and so that subjective bias is within us,” Geist said. “But fairness should be the goal.”

COMPOSING FOR CLICKS

According to a Pew Research Center analysis conducted during the 2012 election, the right-leaning Fox News Channel’s coverage of Obama was negative 46 percent of the time. Left-leaning MSNBC’s coverage of Republican Presidential Candidate Mitt Romney was negative 71 percent of the time. These biases still exist, and even reputable legacy media such as The New York Times came under fire after the 2016 election for ruling out a Trump victory.

“I noticed that on election night and the subsequent days, the media seemed entirely shocked, since I don’t think any of them believed that a Trump presidency would be a reality,” said Ralph Paz, a junior studying political science and history.

However, biased reporting is not the same thing as calculated, incorrect reporting, and Paz said he doesn’t believe in the so-called “age of fake news.”

Carr, however, discussed financial factors incubating fake news in ad-based revenue models.

“Some people are just reporting fake news for the money,” Carr said.

She pointed to a “fake news” story written by Cameron Harris, a man infamously known for his fabrication of fake stories for profit during the election. The headline he fabricated read, “BREAKING: ‘Tens of thousands’ of fraudulent Clinton votes found in Ohio warehouse.”

The New York Times reported that he made about $5,000 off the traffic on his site, and all from a story that had only taken him 15 minutes to craft.

Sam Terilli, former general counsel to The Miami Herald and journalism and media management department chair, said he believes social media played a large role in spreading these false stories.

“‘Fake news’ is troubling. Let’s call it what it is – lies,” Terilli said. “Social media has enabled it and has technologically facilitated it.”

Terilli said that this was not a partisan issue as much as it was an attack on credibility. Sensationalized, untrue stories reinforce the preconceived notions and prejudices that people have about specific issues, he said.

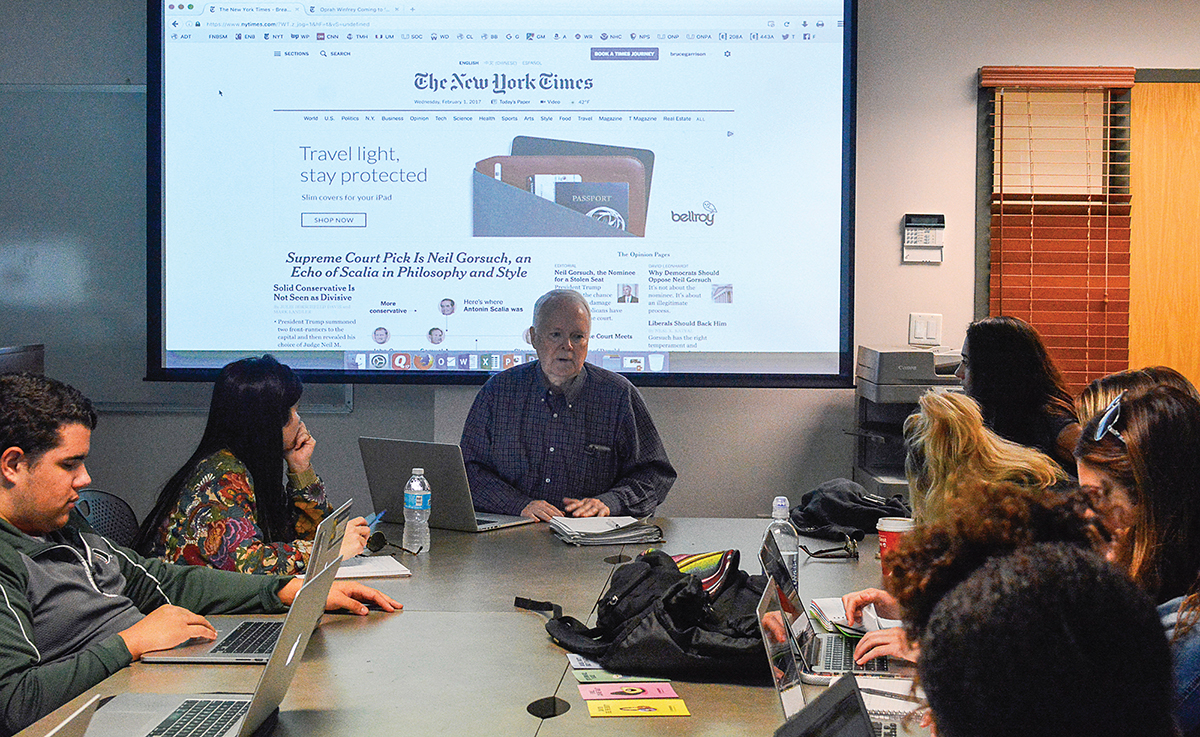

As the professor of Freedom of Expression and Communication Ethics, a course focused on the evolving news industry and First Amendment rights, Terilli compared “fake news” to false advertisements. In advertising, unethical behavior leads to the fabrication of falsehoods intended to sell a product. In the case of “fake news,” the desired end is traffic, clicks and ad revenue.

“It is a means to an end, where the prospect of more ad revenue leads to more and more of these fake news stories,” he said.

Amanda Herrera contributed to this report.