Before Marco Rubio debated with Donald Trump and Ted Cruz in the Republican presidential primaries, the U.S. Senator from Florida quietly honed his debating skills at the University of Miami School of Law.

The Miami-born candidate for the Republican nomination attended the law school from 1994-96, when he graduated cum laude with a Juris Doctor degree. On March 10, he’s expected to return to the Coral Gables campus to participate in the Republican presidential primary debate. The event will take place five days before the primary in Florida, the state that’s considered a must-win for Rubio to stay in the race. Rubio has won just 110 of 655 republican delegates so far, according to the Associated Press.

Rubio, who could not initially be reached for this story, impressed his ambition and competitive nature upon students and professors while at UM. Former members of UM’s international moot court program, a student program that competed in competitive mock trials locally, regionally and nationally, said that he seemed like someone who wanted to hone his debating skills.

Stephen Martyak, who was a year ahead of Rubio and the program’s vice president at the time, recalled that after debating a case with Rubio, he had the rare fear his team might have lost. Martyak’s team won, but he was impressed with his younger counterpart.

“I can remember wiping my brow [when we won] and saying, ‘Whew, we beat him,’” Martyak said. “He was good, there was nothing phony about him. He was ferociously competitive, but played by the rules.”

Martyak and the program’s president at the time, Siobhan Morrissey, had competed against Rubio in a pitched trial of two made-up countries that were disputing an environmental issue in front of the International Court of Justice. The case was a part of the 1995 Philip C. Jessup International Law Moot Court Competition.

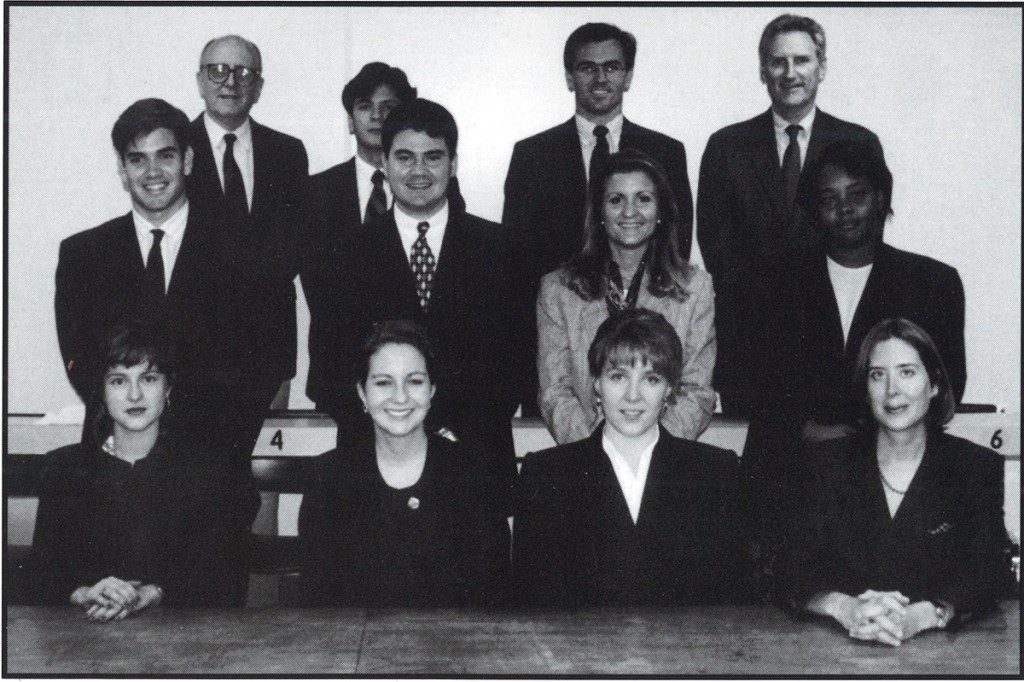

Morrissey and Martyak agreed that Rubio had shown an unusual ambition just by joining and competing in the international moot court. The program, according to Morrissey, had been dormant for years; in the law school’s 1995 yearbook, Rubio is listed as one of just 12 students involved.

“[International moot court] was not something many people knew about,” Morrissey said. “Anybody who participated in this really was a go-getter because it wasn’t something that was easy; there’s a lot of work involved with this.”

Morrissey and Martyak said the program, which has grown to include more students today, was “niche” at the time because of its previous dormancy.

“The fact that he was in this, this was extracurricular, you had to volunteer to do this extra work, with no internet, going up to the library to find information,” Martyak said. “He was really good when it was hard.”

Morrissey said that they sometimes spent up to eight hours in the Law School Library, searching for evidence, and past briefs that won the competition, to back up their argument.

“It involved both the law and putting it in current-day context,” said Morrissey. “Not only did we have to put together a oral argument, we had to put together a brief, and it had to have very specific criteria, even to the actual font that we used and the size of the font. It was very particular as to the number of pages and something that, when you’re working with a group of people, you have rely on other people to do their bit too.”

Professor Richard L. Williamson Jr. recalled teaching Rubio in a class about international law at UM. Williamson said he would give students a problem involving current issues in international law and they had the option to either write a 10-15-page paper or to debate. Rubio chose to debate.

“I do remember that he was very well-spoken,” said Williamson, who couldn’t recall personal interactions with Rubio due to the size of the class.

The recollections students and faculty provided of Rubio paint the picture of a quiet and driven student, focused on his academics and taking aim at political office after graduation. Associate Dean of Students William P. VanderWyden III said that, although he met with Rubio multiple times, he could only recall that Rubio was focused on his academics as a student.

Rubio said his time in the international moot court gave him a unique chance to advance his skills in debate and foreign policy.

“Participating in the International Moot Court Program was a highlight from my time in law school. It gave me the unique opportunity to apply my interest in international issues, that was inspired by my grandfather, and strengthened what would become a life-long passion for foreign policy, all the while developing both my written and oral advocacy skills,” said Rubio. “I’ve always been a competitive person, but debating cases certainly reaffirmed my desire to fight for solutions to the problems facing my community, state and country through public service. As a participant, I needed to think critically and challenge policy, both of which are skills I use today as a U.S. Senator.”

Rubio’s ambitions were consistent before, during and after law school. While attaining his degree in political science from the University of Florida, Rubio worked in the offices of U.S. Representative Ileana Ros-Lehtinen of Florida’s 27th congressional district and State Sen. Lincoln Diaz-Balart. In the spring of 1996, he volunteered on Bob Dole’s 1996 presidential campaign alongside Florida Lt. Gov. Carlos Lopez-Cantera.

“He was a lot like he is now: very down to earth, just a regular guy,” Lopez-Cantera said. “We were all there just for a common purpose; we all bonded over that.”

For Rubio, his purpose was to change the world through public office, as he has said on his law school application. According to his memoir “An American Son,” Rubio put on his application that he wanted to create a new legal and political system in “a free Cuba.”

Rubio was active in the Hispanic Law Students Association, Mock Trial Team and Litigation Skills Program, according to the Miami Law Magazine, although he is listed only as a member of the International Moot Court in the 1994, 1995 and 1996 editions of “Amicus Curiae,” the law school’s yearbooks.

By 2000, just four years after he had graduated from law school, Rubio was elected to the Florida House of Representatives. Now 44 years old, Rubio is the first graduate of UM’s law school to run for the office of president. Those who knew him aren’t surprised that he’s running.

“It is not surprising that [the first UM alum to run for president] is Mr. Rubio. He was quite taken with politics, as I recall, and a leader in many aspects of student life,” Edgardo Rotman, the faculty advisor to the International Moot Court, told the Miami Law Magazine in a 2015 article.

This story has been updated with a comment from U.S. Senator Marco Rubio.