Throughout February, United Black Students (UBS) has collaborated with other organizations to host events celebrating Black Awareness Month, widely known as Black History Month. Next year will mark 50 years since UBS was founded at UM and became a force for change on campus.

Although UM was one of the first southern colleges to integrate when it opened admission to all students in 1961, there were no black professors until Whittington Johnson was hired in 1970 in response to student protests.

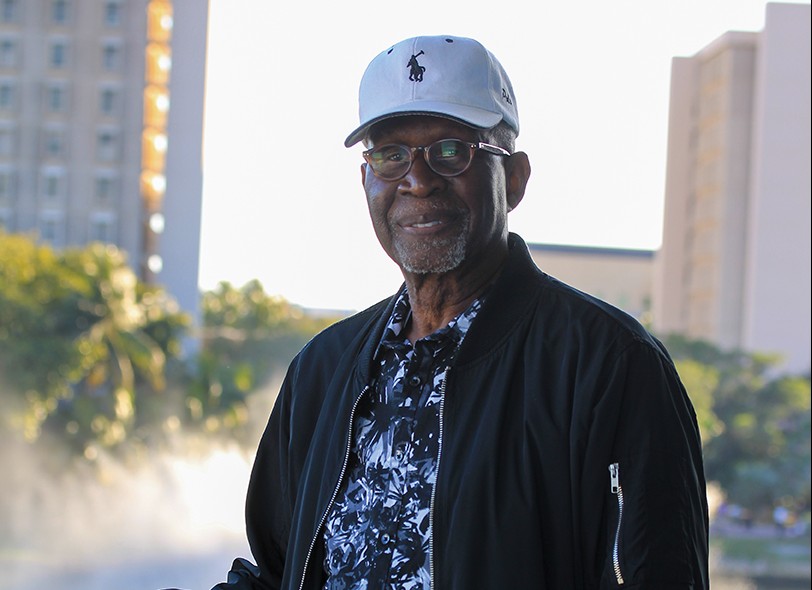

Johnson, who is now 84 years old, has an extensive resume: professor emeritus, three-time history department chair, director of the African-American Center (which existed at the time), member of the Iron Arrow Society and first black professor at UM.

He was born in Miami to Bahamian parents and attended local public schools, becoming vice president of his graduating class from Booker T. Washington High School. He was the first person in his family to receive a college degree, graduating with a bachelor’s degree in history from West Virginia State College and went on to become second lieutenant in the Army Reserve – the only black officer on his base – for two years.

“Indeed, the Army helped me in more ways, but I know the one – among the things it taught me was respect for subordinates, people in subordinate positions to me,” Johnson said. “And I remember that; that stuck with me to the extent that when I started teaching, I would not dare embarrass a student in class.”

Although his original intention was to go into law school, Johnson said there was a turning point in his life when he attended the University of Georgia. He decided that he not only wanted to become a history professor, but also wanted to become a historian.

“And that’s the good thing about the University of Miami: it allowed me to do that … I was able to go to the Library of Congress to do research, the British Library to do research, in the Bahamas to do research and as a result of that, I was able to get four books and a lot of articles,” Johnson said.

Despite the turbulent times on campus before his arrival, Johnson said that all of his 32 years at UM went very well, from his first day in 1970 to his last in 2002. He was hired as a black professor but seldom taught black history – only once every two years – and filled his time mostly with other history courses.

Johnson said the students he taught were intelligent, hardworking and embracing of the uniqueness of his position as a black professor, and some even grew long-term friendships with him.

“I always looked upon my students as my adoptive sons and daughters. And we developed a kind of relationship that many of them come by. We talk for a long time and so forth, and even today,” Johnson said.

He was asked to become chair of the history department in 1976 and accepted the position, but stepped down a year later after a disagreement. Johnson wanted to establish a pay scale for the professors, ranging from associate professor to tenured professor and beyond, but the university did not agree.

“I guess I was idealistic. I’m an Army man so basically, in the Army, you take care of your men, you know? I felt the same thing. A chair, it’s my job to look after my professors,” Johnson said.

The level of respect with which he tried to treat his colleagues and students stemmed from a mindset of not making distinctions between people of different races, backgrounds or positions, Johnson said. As an officer in the Army, the majority of his subordinates were white men. At the University of Georgia, it was a very similar situation.

“By the time I got here, I was ready. I was seasoned, not even realizing though, that I was seasoned,” Johnson said.

Johnson said at one time, of the 364 faculty members in the College of Arts and Sciences, he was the only black person. As time went by, however, the university slowly recruited more black faculty members. In many ways and at many times in his life, Johnson was a barrier breaker and his commitment to teaching at UM helped to lead the way for better integration.

“I don’t know whether hiring me was an experiment, but I think what it may have done anyway, it may have made it easier for them to bring other folks in because basically, I didn’t lay an egg,” Johnson said.

However, pushing the university forward and forging a way for other black scholars was not his goal when he became a professor, Johnson said.

“My goal here was … I would one day want to write an award-winning book, which I never did. But it was never paving the way for others. I just didn’t look at it that way,” Johnson said.

On Dec. 3, 2015, President Julio Frenk announced in a letter to the UM community his initiative to diversify the university. The letter said the university would work to admit and to matriculate the largest percentage of black students among our “peer institutions” and to recruit more black faculty.

According to Johnson, the lack of diversity among faculty is not necessarily because of an opposition to people of non-white backgrounds.

“It’s not because they’re opposed to having black colleagues, but at the University of Miami, most of the departments are understaffed,” he said. “And their primary goal is to fill vacancies in-field.”

This means hiring the candidate who can meet the need, regardless of their gender, race or ethnicity. Johnson used the example of history professor Donald Spivey, who is black. He was hired as the chairperson for the history department in 1992 and still teaches at the university.

“But they didn’t hire him because he was black. They hired him because he was the best of the candidates,” Johnson said.

The same standards apply now as the university aims to take in more black students and faculty. The requirements for admission or for employment remain the same, but the university is forced to “look at it hard and do it.”

“I think most of the elite schools in America reflect this diversity to some extent. It’s hard to defend the position that there aren’t qualified black scholars, women or Hispanic scholars to fill these positions,” Johnson said.

As February and Black History Month both come to a close, the question arises of what it means to celebrate the accomplishments and contributions of black people.

“My thing on this is that, have Black History Month – but teach black history the year round,” Johnson said. “A group that relies upon another group to tell its history probably will be excluded from the narrative.”

Until then, his remedy for the problem of racial stereotyping and stratifying is what he has based his whole life around: education. Multicultural education in schools and even simple interactions among people of different backgrounds can help to break down walls of prejudice in society, Johnson said.

“You’re immersed in it. All of a sudden, it’s not a thing out there, it’s a real living individual. But that’s the key: the key is to getting a better understanding,” Johnson said.

Correction, Feb. 29, 2016: This story previously said Johnson is 82 years old. Johnson is 84 years old.