Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders believes that “nobody who works 40 hours a week should be living in poverty.”

However, this seems to be the case for typical low-paying jobs that offer workers starvation wages that cannot possibly permit them a decent standard of living.

According to the Economic Policy Institute, worker productivity since 1973 has increased by 73 percent but has led to a wage growth of only 9 percent. This disparity between effort and reward has fostered rampant income inequality, and this inequality has become a pressing issue in the 2016 election.

To ameliorate this problem, several politicians have suggested raising the minimum wage, which currently has the same value in terms of real dollars as it did in the ’80s and is the lowest among developed nations.

The knee-jerk response regarding this topic is similar to Republican presidential candidate Dr. Ben Carson’s claim that “every time we raise the minimum wage, the number of jobless people increases.”

The argument is simple: employers demand that workers and households supply labor. Thus, the invisible hand will move the market price of the worker’s wage to a fair equilibrium. If the government sets the wage above the market equilibrium, firms will opt to hire less workers, while if the wage is set below the market equilibrium, the law will have no impact whatsoever.

However, a widely acclaimed study by Princeton University’s Alan Krueger and University of California, Berkeley’s David Card conducted in 1998 lends some surprising conclusions. The study compared employment rates between New Jersey, which raised its minimum wage from $4.25 to $5.05 (about $7.25 to $8.60 in today’s dollars) and Pennsylvania, which opted to leave its minimum wage at $4.25. The researchers found that raising the wage floor does not necessarily mean bleeding jobs. In fact, relative to stores in Pennsylvania, fast food restaurants in New Jersey increased employment by 13 percent while employment for high-paying jobs was unaffected.

Evidently, actual labor markets are far more complex than those modeled by college freshmen in Econ 101. Possibly, this is partially because workers who receive a higher pay will spend their salary and fuel further economic growth through consumption, creating more jobs as a result.

It is also true that there is a certain quantity of indispensable workers needed to maintain a business and instead of firing them, employers might seek to cover the new costs by, for example, raising prices. Nevertheless, this inflation could potentially be mitigated by reduced costs due to decreased employee turnover. Not only would firms spend less on hiring, training and firing, but they would also see an increase in productivity ascribed to more satisfied workers. Therefore, as productivity increases, increasing revenues would give firms the ability to decrease prices once again, making the effects of inflation negligible.

Furthermore, studies show that increasing the minimum wage does in fact lift people out of poverty. University of Massachusetts economist Arindrajit Dube found that increasing the minimum wage from $7.25 to $8.00 reduces the percentage of people living in poverty by 2.9. Consequently, fewer people would be receiving government subsidies, giving Congress the option to either balance the budget slightly more or to allocate that money elsewhere in order to bolster economic growth through fiscal policy.

Despite all this, it would also be naive to conclude that raising wage floors extensively without giving firms time to adapt would not have any adverse effects. If, for example, inflation spurs uncontrollably, some firms would go out of business and higher wages would be dissolved in terms of real dollars. At some point, this type of extreme policy could kill jobs. A wiser approach would be to implement wage increases gradually over an extended period of time to minimize risks.

While augmenting the minimum wage is far from the ultimate solution to America’s current income inequality problem, moving away from oversimplified economic principles when voting is a crucial step toward alleviating the many challenges our less-fortunate citizens face.

Manuel Alcala is a freshman majoring in economics and political science.

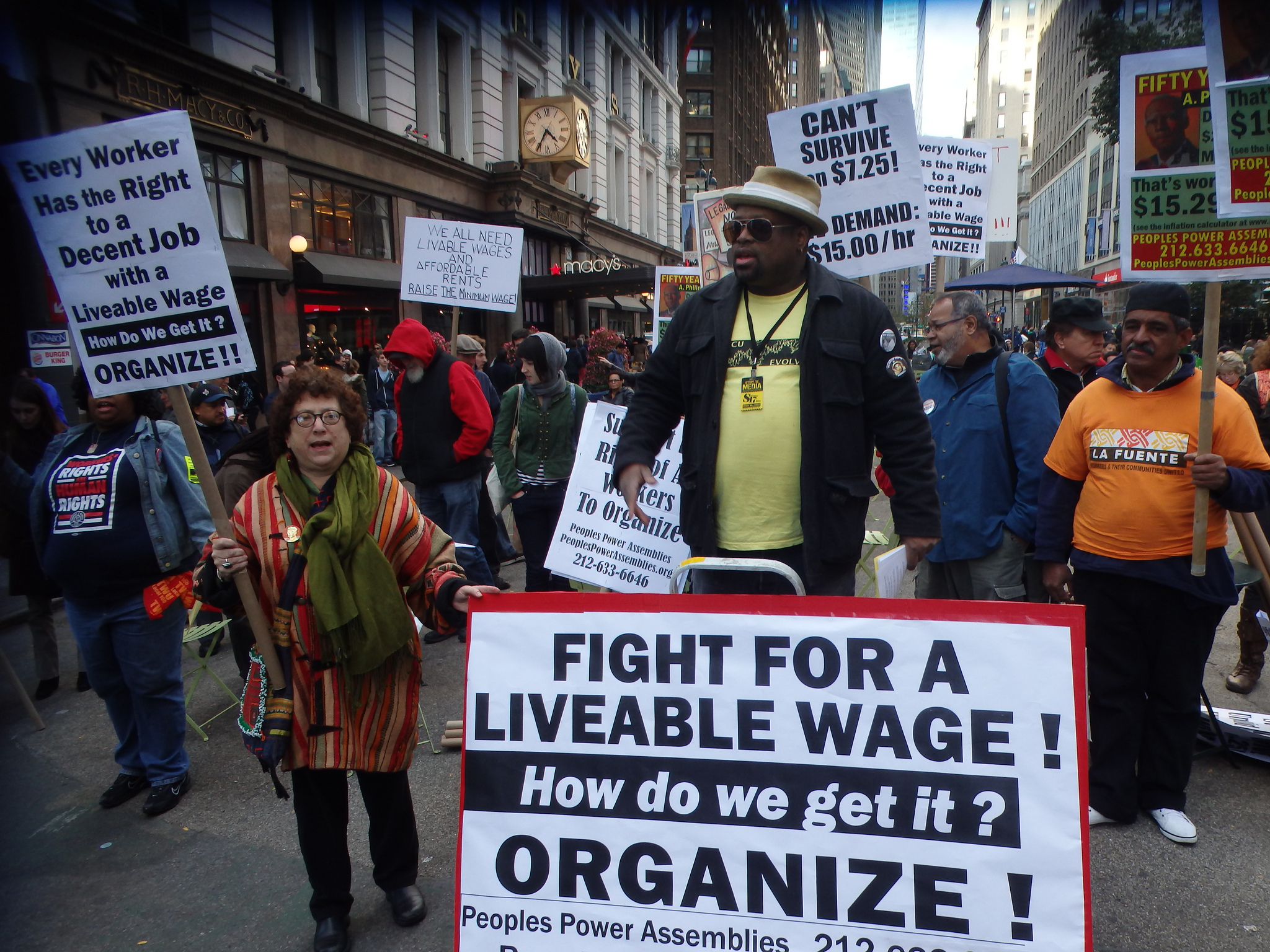

Featured photo courtesy Flickr user The All-Nite Images