Lately, I have been meditating on the meaning of words. I’m not talking about dictionaries and flashcards, but rather the silent, often profound implications that our words carry.

When I first read about the harrowing string of hate crimes happening at the University of Missouri, my initial reaction was one of vague and profound unsettlement. That was all I could say – it was unsettling.

But “unsettling” is a cop-out word. You say it when something horrible happens to somebody else, and you need to convey some form of ground-level sympathy to avoid being labeled by society as cold and unfeeling. “A police officer mistook his gun for a Taser and killed an unarmed black man? Oh dear, how deeply unsettling.” There. Now your debt of sympathy has been paid and you can walk away feeling good about yourself for possessing such unbearably low standards of understanding.

As much as people want to believe that merely acknowledging the existence of discrimination is in itself a means of dispelling it, that’s just not how the world works. And in case you were wondering, flat-out denying that racism is alive and well in today’s society is not acceptable either.

Hell unraveled at the University of Missouri through the promise of a school shooting, anonymous death threats to black students, student arrests, an eight-day hunger strike, public protests and a volatile atmosphere indicative of an extreme level of social unrest. In his letter of response to Missouri students, Chancellor Richard Loftin alluded to the university’s core values: respect, responsibility, discovery and excellence, stating that these values “leave no room for bias and discrimination.”

While it’s nice to think that carving big, progressive terms into stone and calling them “core values” will cause any brazenly bigoted students to take a step back and immediately reject the centuries-old notion of white supremacy, the chancellor’s response more closely resembles what one Mizzou student called a “polished piece of politically correct garbage.”

Also, let’s be clear, chancellor: calling repulsive hate crimes “acts of bias” is like calling Watergate a little white lie. So strap on your big boy shoes, take the silver spoon out of your mouth and start treating this situation and the students you are meant to represent with the proper level of respect.

This pattern of behavior – also exhibited by the University of Missouri’s now-former President Timothy M. Wolfe, who resigned on Monday amid protests spurred by his gross inaction following reports of intolerance on campus – is nothing new. In fact, the United States has been systematically degrading black individuals for centuries.

Knowing this, the question that burned in my mind was: how? How have we as a nation allowed such blatant racism to persist for so long? Why do we condone rather than condemn inaction on the part of the people who are meant to protect us?

The answer is that racism eludes lawfulness and, often, our consciousness of it. Racism is the undying and amorphous cancer that lives in legal loopholes, ousting all attempts to hinder its influence and thriving on the ignorant minds of those who have mouths but no thoughts. We see it in the act of gerrymandering – redrawing district lines to discriminate against a group of people – that, despite its illegality, is a favorite pastime of politicians. We see it in our prisons, in which 60 percent of incarcerated individuals are people of color, even though only 30 percent of our nation matches that demographic. We see it in the continual slandering of our president, who – despite disproving all of the insane accusations regarding his religion and country of birth – will never stop being called a Muslim foreigner. This story has roots in the very beginnings of our country.

As the Civil War came to a bloody close and the institution of slavery was thought to have met its end, the Jim Crow laws were right there to knock equality off of its pedestal and to introduce black Americans to a new brand of derision – one that spoke not through proclamations and legal jargon, but through the subtle torture of insistence. Law is secondary to belief, and when the overwhelming majority of Southerners were set on keeping their former property in their place, equality was impossible. Slavery withered and gave life to its posterity, segregation, which reigned with the same cruel spirit.

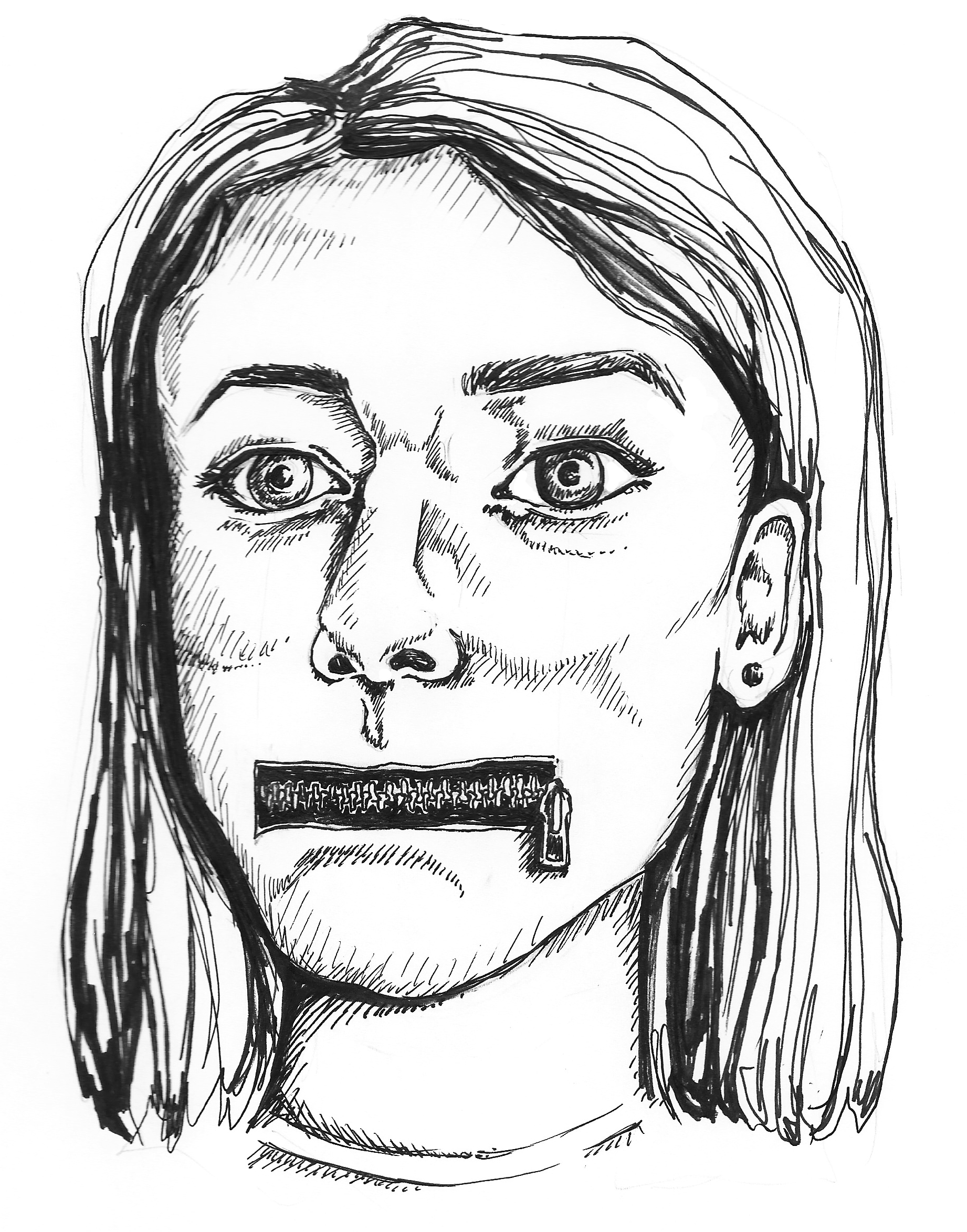

When the Civil Rights Act stomped that out in 1964, racism was weakened but in no way defeated and learned to persist in the silence of others. Today, it lives behind the closed lips of Congress, which never succeeded in passing any of the 200 anti-lynching bills that came its way. It lives inside the bullets that fly through beautiful black kids playing with small plastic guns in the park. It lives in the employment disparity between Joshua and Jamal. It lives in the potency of the racial slurs hurled at Payton Head and it thrives in the debilitating silence that has suffocated the bemused President Wolfe and Chancellor Loftin.

Simply stated, racism exists because, too often, we reject the idea that breaking the silence can make a difference. Because we refuse to confront our own prejudices. Because doing nothing is easier than doing something. It is time for this kind of thinking to end.

Concerned Student 1950 – an activist group spearheading the fight to end racial hostility on college campuses that is named after the year in which the first black student was accepted into the University of Missouri – has stood strong all the while, protesting peacefully and effectively to make their message heard. Currently, students of color and student allies across the United States are declaring their solidarity with Missouri students on social media, adding: “To those who would threaten their sense of safety, we are watching.”

While students, administrators and police attempt to quietly pick up the pieces and bring solace and dignity back to Mizzou’s flagship campus in Columbia, a group of students can be found huddled in a field, linking arms and swaying as they sing “We Shall Overcome” – the anthem of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s – a haunting declaration of the distance we have yet to conquer and a beautiful emblem of the direction in which we are moving.

Mackenzie Karbon is a freshman majoring in jazz performance.