Sophomore Beja Turner has never been taught by a black professor at the University of Miami.

“I rarely see them in any of our colleges and schools on campus outside of the Africana Studies department,” said Turner, a public relations co-chair for United Black Students (UBS). “My experience on campus has shown me that there’s a deficit in black teachers at UM.”

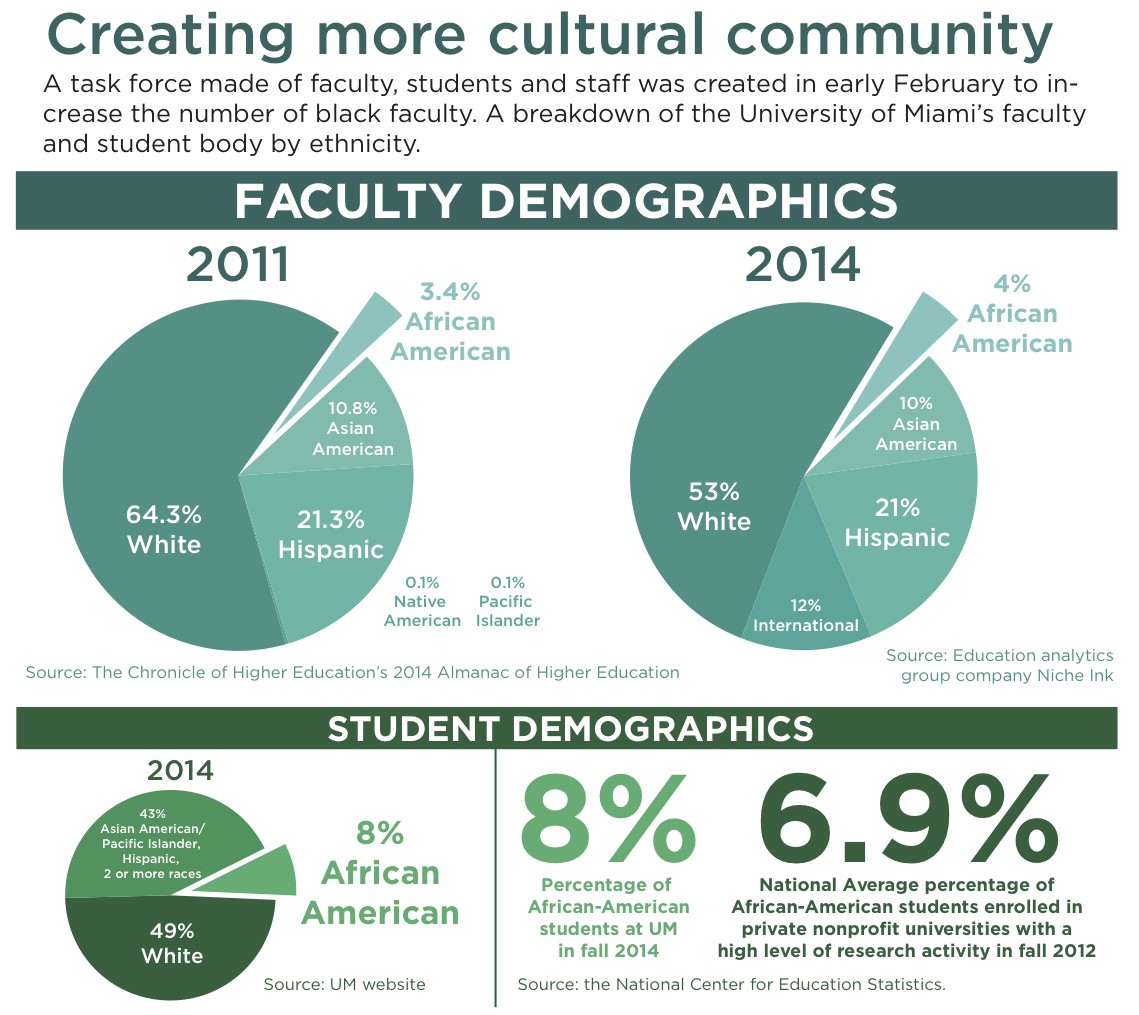

According to the education analytics company Niche Ink, about 47 percent of UM’s faculty identify as another race other than white. Of this total, 4 percent identify as African American.

At the onset of Black Awareness Month (BAM), President Donna E. Shalala called for a task force to recruit more black faculty. Now, a “Task Force to Address Black Students’ Concerns” aims to review current efforts in diversifying faculty as well as assess the campus climate for black students.

The percentage of black faculty members at UM is comparable to universities of similar size and caliber, such as Boston College and George Washington University, according to Niche Ink. These are four-year institutions with a student body of about 10,000.

Unlike these schools, however, UM has almost five times the number of Hispanic faculty.

While Shalala hopes to raise this percentage, UM has, in fact, increased the diversity of its faculty in the past four years. In 2011, about 36 percent of UM’s faculty identified as a race other than white, and 3.4 percent identified as black, according to the Chronicle of Higher Education’s 2014 Higher Education Almanac.

Brian Blake, vice provost for Academic Affairs and dean of the Graduate School at University of Miami, is leading the task force.

“You really need to have all these different perspectives at the table, so you have the ability to shape our academic programs,” he said.

Blake estimated that about six black faculty were hired in the last three years. While this number may seem low, it becomes more significant considering 32 faculty members were hired in total, many by the College of Arts and Sciences.

“Compared to other universities in the, let’s say, top 50, our numbers are actually pretty good for black faculty,” Blake said. “But that being said, that’s not anywhere near what our student body is or representative of what the population demographics are.”

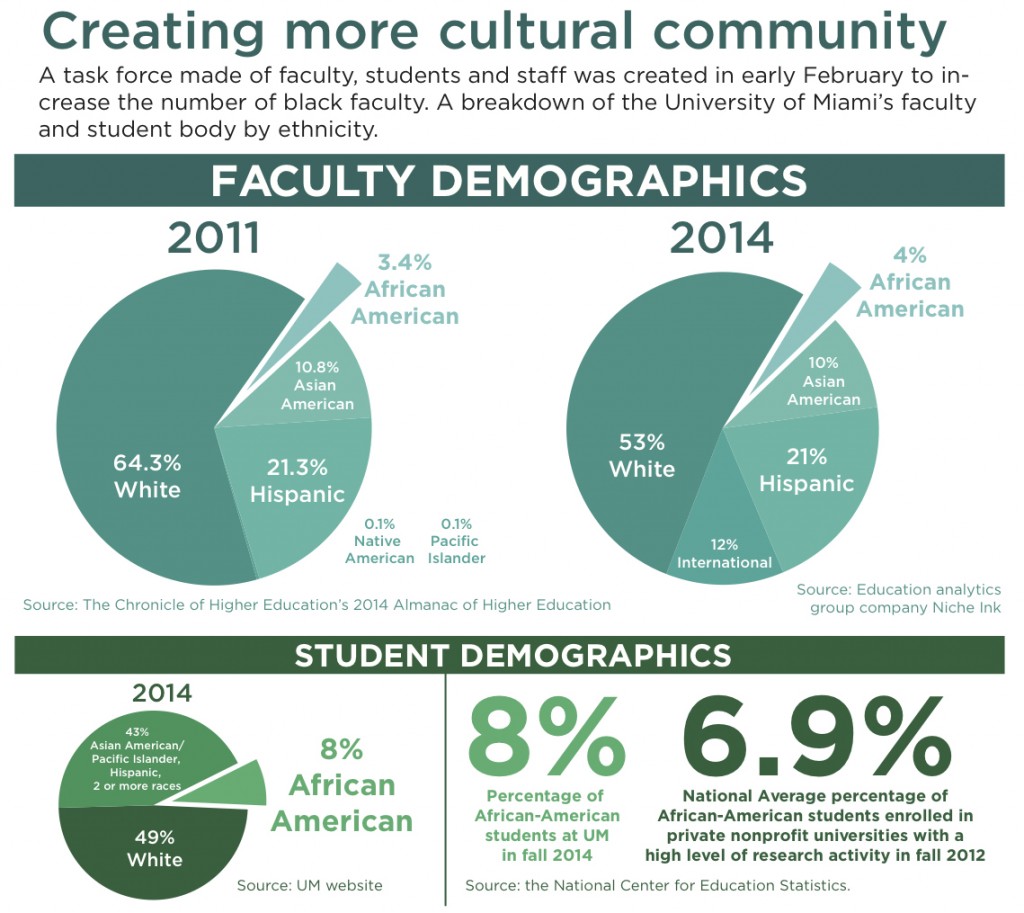

UM’s student body has consistently been ranked as one of the most diverse campuses in The Princeton Review’s Best Colleges list. About 47 percent of undergraduate students enrolled in fall 2014 identified as a race other than white, according to UM’s website. This has not shifted widely since 2010, when The Princeton Review named UM the most diverse school in the nation.

Of this 47 percent, 8 percent of 11,273 undergraduates (or 856 students) enrolled in fall 2014 identify as black. This is slightly above the national average 6.9 percent of students who enrolled in private, nonprofit universities with a high level of research activity in fall 2012, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Blake is coordinating the task force with Thomas J. LeBlanc, executive vice president and provost. LeBlanc specified that the task force will focus on solving the underrepresentation of black faculty.

However, black faculty members like Nicole Yarling view their underrepresentation as a more universal problem.

“I think it’s a great idea to diversify faculty and have people from all over,” said Yarling, a lecturer in the Frost School of Music. “The important part, besides academics, is the socialization of the students, and they need to be exposed to people other than themselves, because they need to go out into the workforce.”

As a student, Turner agreed that exposure to diversity as a college student will prepare her for work in the outside world.

“Having a diverse faculty allows for you to learn things through different cultural lenses, offering a multi-faceted outlook on life and history,” she said. “I believe that learning in this way is highly beneficial for students as we go out to work in this increasingly globalized world.”

The task force is, however, not directly responsible for the hiring of faculty. That job belongs to the academic departments. The task force will instead encourage departments to consider diversity as a key factor in recruitment and provide incentive programs to retain minority faculty members after hire.

“Representation is important in every aspect of life,” Turner said. “If there is no one to look up to that reminds you of yourself, sometimes people don’t find anything to aspire to. That is why it’s so important for students to identify with their professors.”

The task force’s initiative was devised to be self-sustainable, allowing for its continuation throughout the years. LeBlanc described this as a “pipeline” that involves a chain of inputs and outcomes that feed into each other. In the context of maintaining faculty diversity, this means that incentives would lead to retainment, which would in turn support an influx of minority faculty over the years.

“We’re helping to build the pipeline by training the next generation,” LeBlanc said. “That’s why it’s somewhat of a long-term effort, too.”

By preserving the longevity of the initiative, the task force aims to prevent the fluctuation of minority faculty numbers.

At his prior position in the University of Notre Dame as the associate dean of engineering, research and graduate studies, Blake noticed that the two to three black faculty members hired were offset by the four that left for a lack of retention incentives.

The creation of a pleasant working climate will be vital to ensuring retention. Yarling says this will inevitably benefit both students and staff.

“It’s a win-win situation,” she said. “Not only for faculty looking for employment in such a prestigious university, but also for the students.”

However, success in retainment is easier said than done, so maintaining consistent diversity can prove to be a challenge.

“This is a hard problem,” LeBlanc said. “If it were easy, then first of all, we’d have done it, and every other university would have done it. But if you look around and see, we’re at seven percent [of black faculty] and [other comparable research universities are] all at three percent, so we must be doing something right.”

The task force plans to meet to start coordinating efforts this month but has not established a quantifiable goal for the desired increase in black faculty. Instead, the emphasis is on increasing without limitations.

“When we get to a point where ‘more’ doesn’t seem like the right goal, we’ll worry about it,” LeBlanc said. “But we don’t think we’re there yet.”

Alexander Gonzalez contributed to this report.