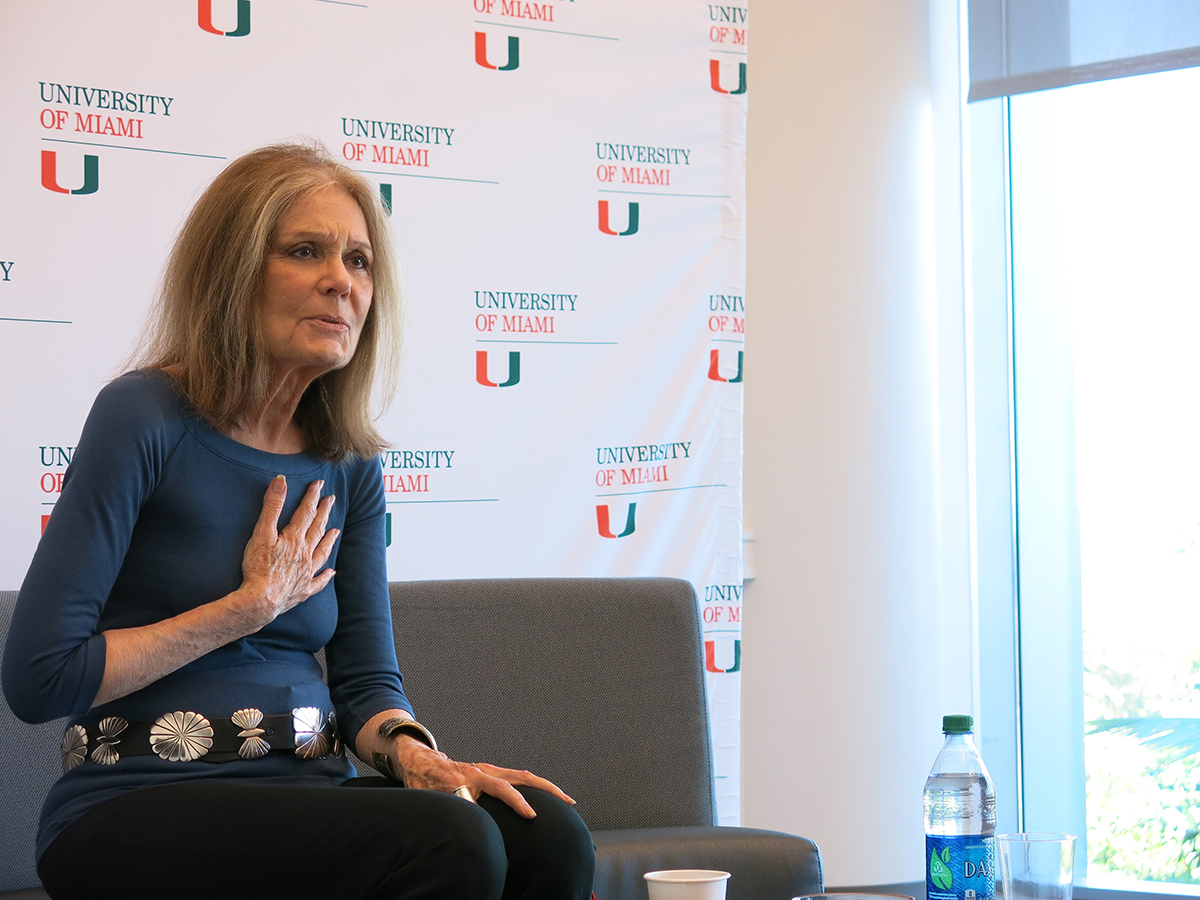

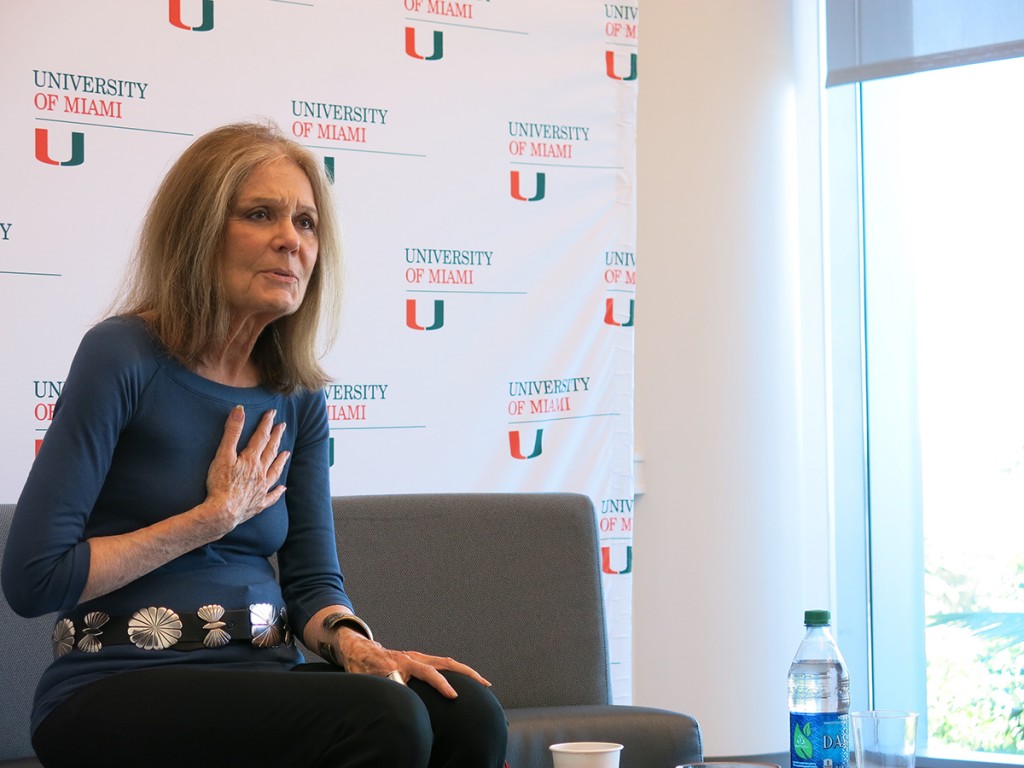

Feminist activist and writer Gloria Steinem visited the University of Miami on Tuesday to speak to a crowd of students, professors and locals at “An Afternoon with Gloria Steinem,” presented by President Donna E. Shalala and Books & Books. During the lecture, Steinem spoke to the crowd about subjects ranging from police brutality to education.

Beforehand, she spoke to members of student media about some of the important issues today’s feminists face.

Student Media: How is our ability to define our own feminism helpful to the movement and how is it a hindrance?

Gloria Steinem: Feminism is just a way of saying we’re all human beings and we’re all diverse and unique, each of us … It’s interesting on campuses because, in the past, people would say, “Are you a difference feminist or are you an equalist feminist?” and I would say, “Yes,” because it depends on the situation.

SM: With celebrities taking on feminism and speaking about it in the media, we get all these different narratives of what feminism is. Is there a space where we need to be critiquing the different narratives or is it really about all of us being able to have our own definition?

GS: Yeah, of course it is. Beyoncé, I think, is great. She’s not had an easy life in a lot of ways. She’s been very isolated by talent and by performance and that she is connecting in this way, I think, is great. I don’t know her. I saw her once at a big concert in London … a benefit for groups working against violence against females. And I realize that there are critiques of her sexualized image and so on, but all her dancers were women; all her musicians were women. She came out in the very beginning and she said to this vast audience of almost totally women, “I know life is hard, but we’re together for this hour and you’re safe.” Okay, she had me. The point is to move forward however we can and to support each other in doing that.

SM: What do you say when women or men say they don’t want to identify with feminism because of the stigma? For example, online on some of the social media outlets there was the “Women Against Feminism” movement.

GS: I think we have to find out why they are saying that. Some are saying it because they really believe that feminism is about hating men, or it’s divisive. I don’t know. If you sent them to the dictionary, they would feel differently. And some of them really are against it. They really do believe that there’s a natural, perhaps even religious, hierarchy in which women need to be obedient and so on. In my experience, the first group is bigger. Once you know that, in a sense, the only alternative, if you’re a female human being, to being a feminist is being a masochist, then I think there’s much more support. We have to recognize the pretty big effort to demonize the word. You know, Rush Limbaugh has been saying ‘Femi-nazi’ for 20 years at least.

SM: How has living in the age of terrorism affected women’s rights and advocacy for equal rights?

GS: I think the age of terrorism springs from the absence of women’s rights. There’s a wonderful book which I’m going to mention in my lecture called Sex and World Peace by one woman and other scholars … They have studied like two hundred countries, every modern country, and very reliably demonstrated that the most important determinant of whether a country is violent within itself or will use military violence against another country is not poverty or access to natural resources or religion or degree of democracy. It’s violence against females.

Not because females are more important than men, but because patriarchy, or whatever you want to call the male-dominant system, means that we see that first often in our own families and it normalizes the whole idea of subject-object … and makes it seem as if it’s human nature, it’s inevitable. And if you listen to the terrorist leaders, the cult of masculinity is really what they’re talking about.

The leader of the 9/11 group left a letter in which he said that a woman was not to touch his body. He had been the son of an Egyptian middle class family and he was kind of slender and “not masculine enough” for the father. The father humiliated him every day by saying “your sisters are more real men than you are.” He went to Germany and got an engineering degree. He wouldn’t accept it from the hand of a woman. In many ways, terrorism is the cult of masculinity at its most extreme … It’s about controlling the one thing they don’t have: wombs and reproduction.

SM: The presence of feminism at the University of Miami isn’t always as strongly felt as it is at other universities. How do you think we could change that and create more of an impact?

GS: Well you who are here, you know much better than I do. Usually, it’s just speaking up, making a small group, picking an issue that affects everybody or many people … and working together on that. Since we’re communal people, since we need each other, nothing is more powerful than a group with mutual support and a vision and a spirit of inclusiveness … You have a feminist president, Donna Shalala.

SM: When you think about ‘action,’ what does that mean to you and how can we translate that into all of our skills and leaning on everyone in a movement?

GS: I think we should worry less about what we should do and more about doing whatever we can … Here’s a good starting question, I think: What do you love to do so much that you forget what time it is when you’re doing it? That you would do it even if you didn’t get paid, though I certainly want you to get paid. And that’s probably your gift, that’s your unique talent. Use that to reach out and say what you care about. Don’t feel you have to learn something up there, although it’s great to learn something up there, but you can be active wherever you are.

SM: As media moves more towards technology, websites can be platforms for the feminist movement, but also platforms against it. For example, the #LikeaGirl campaign aired during the Super Bowl and the reactionary “meninist” page on Twitter that argued that this campaign was anti-equality because there was no #LikeaBoy counterpart. What do you feel about the negative backlash on Tumblr and Twitter and Facebook against the movement?

GS: Forget it. Move forward. What worries me is the threats of violence on the web. I think that we can’t ignore … but, otherwise, Dorothy Parker said, “If what they say be false, do not bother to deny, if what they say be true, stand and scream and swear they lie.” I wouldn’t worry about it too much, just move forward.

SM: What is the lesson that has taken you the longest to learn?

GS: Oh god, so many. Well, you, as writers, will relate to this—not waiting for a deadline. I just stayed up all night last night trying to finish a chapter. It’s like my life is one long sophomore year because I’m a writer. I always think I can do more than I can writing and so I think my time sense is not realistic.

Conflict is very hard for me. I tried to learn from Bella Abzug, who loved conflict—she thought it was exciting and it brought out the best in her, but it just makes my stomach drop. So, if you have something you can’t solve, I would say try to use it. The fact that I was bad at conflict made me a peacemaker.