Thomas Duncan, a 42-year-old Liberian, became the first patient in the United States to die from Ebola. He passed away last month in Dallas after contracting the disease in his native Liberia before traveling to the U.S. A new life-or-death threat like Ebola gives us a chance to reflect on what we’re doing as a country to handle new types of challenges.

Since the arrival of Ebola, we’ve collectively freaked out. Schools turned away students with parents guilty of travelling to West Africa. Calls for isolation in travel bans run ironically viral across the media landscape. Healthy aid workers were quarantined in rampant cases of political theater before elections.

None of this is necessary or constructive, given the tough nature of Ebola’s transmission and its well-managed control by officials in the White House and Department of Health and Human Services.

There is a real, sad truth to Ebola, one that warrants deeper consideration for other problems. Ebola is a terrible disease that most strikes those who care the most.

Duncan contracted the disease by carrying a pregnant neighbor to the hospital when she was too ill to travel herself. A good Samaritan, he paid with his life. Two nurses caring for him in Dallas were infected while in poor safety conditions working at an already undervalued and vital job in our health system.

The only current case in the U.S., Dr. Craig Spencer, was on the front lines with Doctors Without Borders in Guinea when he was exposed. Doctors Without Borders, a Nobel Peace Prize-winning humanitarian organization, has already lost 13 staff members to the disease.

This is the reality of the decentralized world in which we find ourselves. Rising social connections mean that our choices of consumption, travel, career and lifestyle affect others in multiplying fashion.

In an ideal setting, we would be free to practice altruism and socially positive careers without fear of repercussion. But the more we work for others, the more we expose ourselves to the reality of their lives, for better and worse.

Franklin D. Roosevelt once said that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself. In debates between security and trade-offs to freedom and social good that security incurs, it is harder to hear calls for compassion and rational consideration of actual risks.

Indeed, as if by vote-hungry magic, U.S. political winds metastasized Ebola into chest-pumping calls for disengagement from the world by elected officials. Real tough guys, letting fear cloud sober judgment. Like in 2012 after Benghazi. Or in 2008 when the price of gas rose and economy tanked. Or in 2002, authorizing executive powers in homeland security that we are still unraveling.

Our threats are decentralized and our world complex. But this world existed before Ebola, or terrorists, or market shocks. It will exist after the next big crisis, too. And we should not abandon reason and kindness when such a time comes around.

Patrick Quinlan is a junior majoring in international studies and political science.

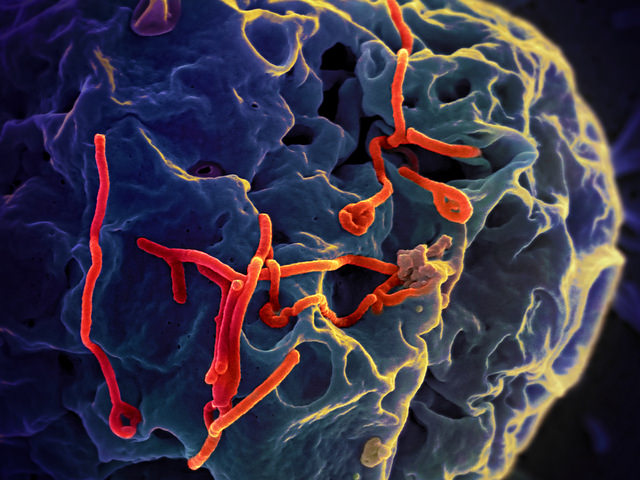

Featured photo of Ebola virus budding from the surface of a Vero cell courtesy NIAID via Flickr.