The hallway in the Miami Children’s Hospital Intensive Care Unit was quiet last Saturday afternoon, save for the constant beeping of monitors. Suddenly that changed. Nurses danced, doctors peered out of rooms to see what all the commotion was, and one little boy grinned from ear to ear as he bounced up and down.

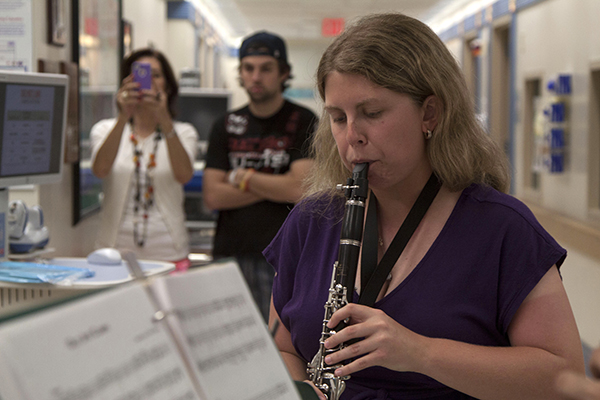

The newfound liveliness in the ICU was thanks to a clarinet performance by three UM students from the Frost School of Music. They are members of the Ress Family Hospital Performance Project, which brings music into local hospitals to lift patients’ spirits.

“The students are just coming in and sharing their gift of music, and the patients love it,” said UM music therapy professor Shannon de l’Etoile, who oversees the project. Although the performances are not formally considered music therapy, they provide relief from the tedious grind of life in the hospital.

“All we hear all day is the noise of the machines,” said P.J. Campbell, a 24-year-old patient with a congenital heart defect. “The Ress performance made my day.”

The project was funded by a 2002 gift from Lewis and Esta Ress of North Miami, after Esta herself was hospitalized and the two experienced the joy of live music.

Today, the project consists of more than 30 Frost students who were either recruited or auditioned. Volunteers perform as soloists or in small ensembles for children and adults at nine hospitals in Miami-Dade County. The musicians play everything from jazz standards to movie tracks, such as Harry Potter’s “Hedwig’s Theme,” and perform in the hallways, moving around to various units, or visiting individual rooms for patients who can’t get up.

For sophomore cellist Vienna Sa, a music therapy major, bedside performances are very rewarding.

“You go into a room every 15 minutes,” she said. “Every 15 minutes you make a connection.”

Sa believes this student-patient engagement is just as important as the music, if not more.

“Patients really open up,” Sa said. “They tell you their life stories.”

Before performing, students receive tips on how to interact with patients in a potentially sensitive environment. According to Marlen Rodriguez-Wolfe, who is in charge of day-to-day operations of the Ress Project, “see you later” is a phrase they tend to avoid because it creates an expectation that sadly may not be fulfilled.

The interactive nature of the project is especially clear when students perform for children, playing “name that tune,” taking requests and answering questions about instruments, some of which the children have never seen.

“It’s a huge distraction for them,” said junior Carlos-Andres Rodriguez, one of the clarinet players who performed at Miami Children’s. “One of the most striking things was going to the oncology ward and seeing children walking out of their rooms with their IV poles to hear us play.”

De l’Etoile said she has seen parents in tears when their children transform from cautious and fearful to curious and playful. In a world where these young patients learn to expect discomfort and pain, it “gives them a moment to share that isn’t about the next chemo.”

The performances don’t affect just the patients and their families. Nurses, doctors and hospital staff often stop to watch, dance or sing. The clarinet ensemble’s recent performance was punctuated with laughter when two nurses tried to coordinate bobbing up and down to the music.

The project has recently expanded to include a hospice ensemble, and de l’Etoile said she hopes it will continue to grow.

Although musicians receive a small compensation for the visits, many of them said the experience is priceless.

“It makes me really happy to see I’m making a difference in their lives,” Sa said.

In fact, that difference might inspire the next generation of musicians.

“I don’t have a clarinet,” said Deborah Skielnik, as she poked her head of bouncing curls out from behind her father’s legs. “I’m gonna buy one with all of my dollars.”