There are 399 people sitting on Death Row in Florida, according to statistics posted on the Department of Corrections website as of Wednesday.

A recent string of exonerations indicates that up to 10 percent of these inmates may be wrongfully convicted.

Gretchen Cothron, the student co-director of the Wrongful Convictions Project (WCP), helped create a law clinic at the University of Miami School of Law in order to more closely investigate cases for inmates who maintain their innocence.

“I came down here to put my boxing gloves on and fight the good fight,” said Cothron, a second-year law student.

WCP was admitted as a member of the Innocence Network in 2011. UM is the only law school in Florida to be included in the network.

As a former forensic scientist, Cothron reviewed cases for innocence projects around the nation. At UM Law, she met professor Sarah Mourer – a criminal defense attorney – and Judge Milton Hirsch. Together, they agreed that South Florida could benefit from a clinic to aid wrongfully convicted inmates.

“It could be a huge impact in the Miami area because of Miami’s history of corruption, drug cases and just being a city where the police are so strained and under so much pressure that they try to solve the high profile cases quickly,” Cothron said. “Sometimes they just want to get somebody behind bars so the community will calm down, and that’s why we’re here.”

Cothron worked closely with Mourer in order to expand the project from a club to a functional clinic. Dean Trish White was also instrumental to the club’s expansion, Mourer said.

“I ran the wrongful conviction club for about three years, and then the dean was gracious enough to let us turn it into an actual clinic,” said Mourer, who also serves as the clinic’s faculty adviser.

The clinic screens letter from inmates who believe they meet the necessary criteria for further investigation. The process to exonerate a convicted felon on Death Row could take approximately three to five years, so Cothron noted that inmates must have at least nine years remaining on their sentences.

Also, investigations are often difficult to conduct because the researchers must find newly discovered evidence. In other words, the defense lawyer could not have found this newly discovered evidence in time for the trial.

Since its inception last year, the WCP at UM has received more than 900 cases for review. Cothron said they have turned away nearly 90 percent of those inmates.

“We hope to educate people so they have an awareness of the issue and do something proactively,” Mourer said. “We also work to create guidelines to follow so people aren’t wrongly convicted in the first place.”

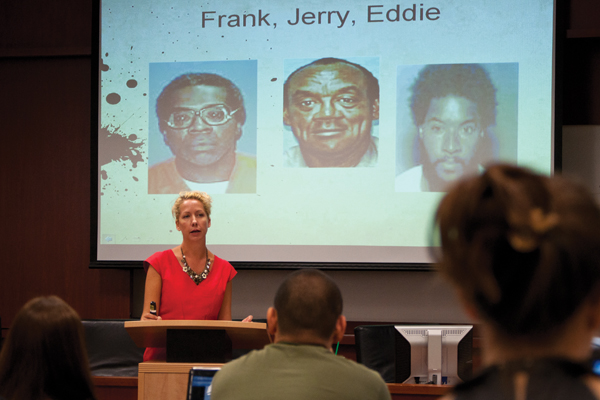

On Tuesday, Cothron and Mourer held a presentation at the School of Law to discuss their progress and their goal to work on more exonerations. The group uses both DNA and non-DNA evidence to help wrongfully convicted inmates.

“The foundation of our justice system is to make sure everyone gets a fair trial,” said second-year law student Beth Gordon, co-director of the project. “In Florida especially, we have a high rate of wrongful convictions. You can’t fulfill this big idea of justice if you’re not actually convicting the right people and conducting investigations properly.”