Muslim students at the University of Miami share some everyday struggles, like getting caught washing their feet in a bathroom sink on campus before attending prayers as part of a traditional ablution ritual. Or watching the dining hall staff handle another student’s ham sandwich and having to find another halal-friendly meal station. Or having the student organization move spaces each year around the constant construction on campus because they don’t have a designated religious center.

With each class of students in Muslim Students of the University of Miami (MSUM), it’s almost routine to ask administration, “Why don’t we have a chaplain? What ever happened to that Islamic Student Center we wanted?”

“A lot of what we know about it has been passed on from other students,” said junior Aaisha Sanaullah about the proposed center, which has yet to be built.

The story goes back to the 1950s, when the university dedicated plots of land to organizations and fraternities in order to develop student life. The one catch was that if the organization stopped using the land to serve the student body, the university could take the land back – a reverter clause.

In the 1980s, the university set aside land for a Muslim student center and, like the other religious organizations, it was the responsibility of the students to raise the money and build on the land. Under the guidance of Moeiz Tapia, the advisor to the Muslim student organization at the time, and with the help of an Islamic Student Center (ISC) Board, William Butler and Vice President for Student Affairs Patricia Whitely, there was a big push to raise money.

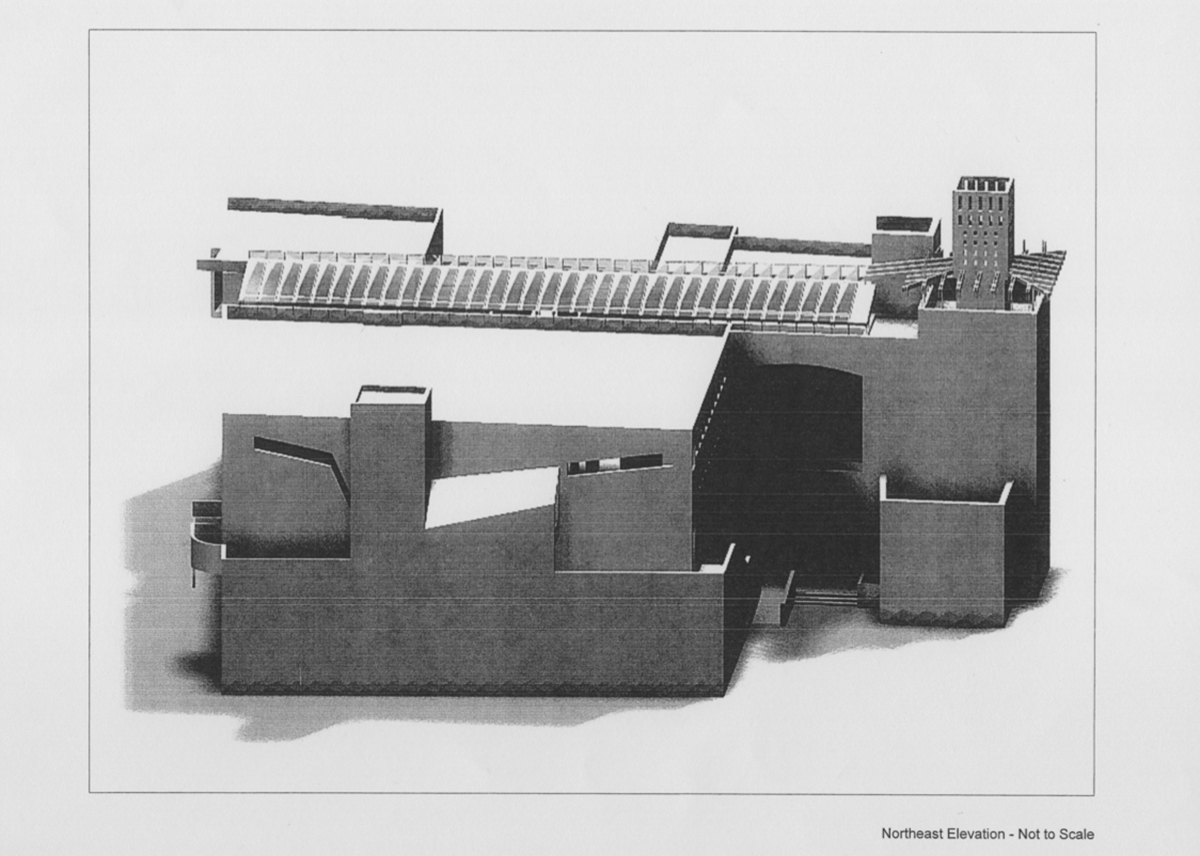

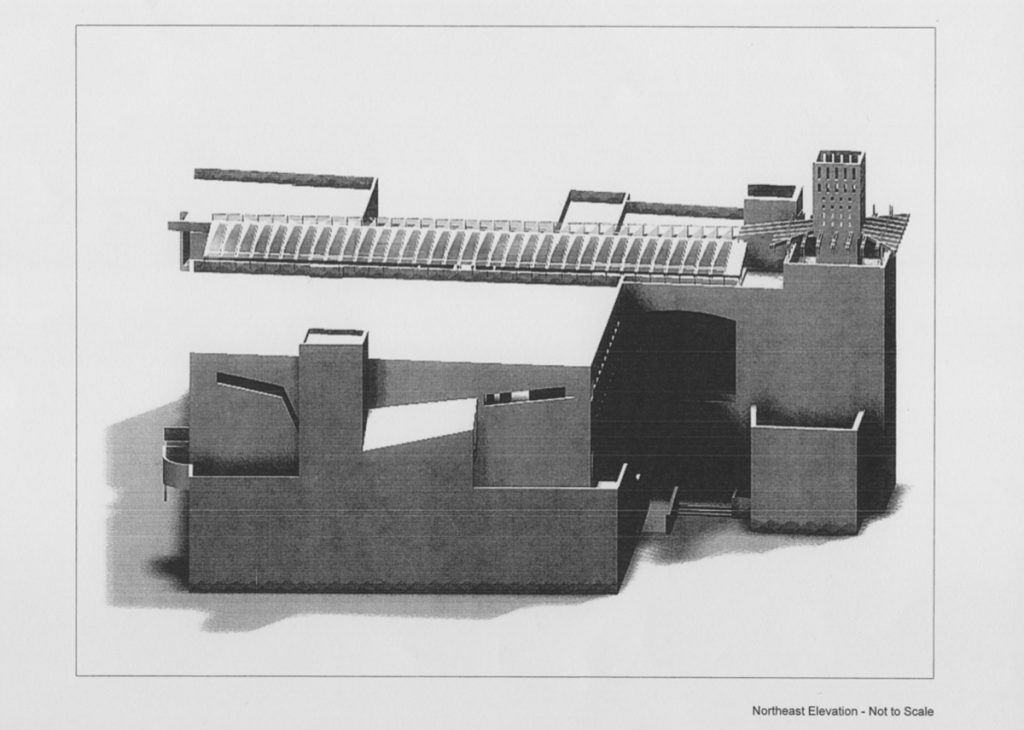

The board raised about $500,000 to design the building and hired renowned architect Gulzar Haider, who then presented three designs to the board. The approved design featured specific units for different activities and a covered breezeway.

Haider, the current School of Architecture dean at Beaconhouse National University in Lahore, Pakistan, still thinks fondly of his time working on the ISC.

Haider described the ISC project as an opportunity to achieve “an architecture worthy of the American spirit of freedom and refined Abrahamic spirituality” in an email.

The total project was estimated to cost $5 million to $6 million in 2001. The cost of the building, the maintenance endowment and the funds for programming and staff all had to be raised independently of the university.

When former President Donna Shalala came to UM in September 2001, she vowed her support, writing letters to donors and making the Islamic Student Center project a university priority. The administration even sweetened the deal for donors by counting a donation to the ISC project as a donation to the first Momentum campaign that launched in 2003.

Yet Shalala, the fundraising powerhouse behind the university’s biggest capital campaigns, couldn’t make it work. The community didn’t back the project.

“I’ve never run into a brick wall like this,” Shalala said. “I’m good at raising money. We just fell really short … it just failed.”

There were obvious hurdles, such as a scarcity of large Islamic institutions in Miami and the strict Coral Gables building code, but an unprecedented event would overshadow those hurdles: Sept. 11, 2001.

“That became an issue after 2001,” said Shihab Asfour, associate dean for academics in the College of Engineering and advisor to MSUM. “The flow of money is not there because people were worried they would be accused of sponsoring terrorism.”

The funds that had been coming from the Middle East and from Muslim families in South Florida froze, and the project halted. Though the 9/11 attacks shook the campus, Shalala said the failure of the project was a result of many factors.

“I arrived that September, but we tried the year after that and the year after that,” Shalala said. “It wasn’t just that. I’m really sad about it.”

As an Arab-American, Shalala felt the need to support the Muslim community at UM in a particularly vulnerable time. After 9/11, the Muslim students got a suite space so they wouldn’t be praying on a patch of grass outside, like they had in years prior. Since then, the students have been moved from building to building, sometimes creating makeshift prayer spaces closer to the center of campus, such as setting up mats in the back of the second floor of the library.

“It’s a struggle and it’s not really anyone else’s fault; it’s just unfortunate,” Sanaullah said.

By now, the original plots of land have been transformed into buildings and parking garages. If the students still wanted to create the ISC, they would need to find land off-campus, a challenge, considering many observant Muslims pray up to five times a day and many students don’t have their own transportation.

“At this point in time, it’s not something that we’re going to pursue,” Whitely said.

The ISC would be an even more ambitious project to undertake now, when the total cost may be double the $9.2 million it would have cost in 2007 and the Coral Gables geography is becoming increasingly cramped with expensive new construction.

It is no longer a university priority, but MSUM alumni like Micelli Bianchini still consider it worthwhile.

“I think that this building is important enough to cut through all the bureaucracy,” Bianchini said in a phone interview.

Bianchini was one of the key student proponents of the project when he started at UM in 2006. He met with university administrators and breathed new life into the idea of the ISC, but that faded again when he graduated in 2011.

“I think the ideas and relationships created from just this one building can work to solve a lot of problems in the Muslim community,” Bianchini said.

The university has invested money in modifying a suite in the LaGorce building across from the architecture school. The space will have an open area for prayer and is expected to be ready for move-in by the fall.

The last thing missing is a chaplain, for which MSUM members say they are most hopeful. The chaplain, a designated imam salaried by an outside organization or seminary, would serve not only as a spiritual guide and teacher for the students but as a campus leader.

“At the end of the day, we’re still students and there are questions we can’t answer,” said freshman Qismat Niazi, a California-born child to Afghan parents.

A chaplain would create more interfaith dialogue with leaders of other religious organizations and foster the congregation of Muslim students by creating consistency. Having one place and one leader would make the Muslim experience on campus much more “seamless,” Sanaullah said.

Instead of finding local imams to visit campus for events and services, Muslim students at UM could have “someone who is our own.” A chaplain could also help the handful of students on the MSUM executive board who try to organize programming.

“Someone to help us shoulder the responsibility because, especially in the last year, with the political climate, a lot of people have been reaching out to MSUM,” Sanaullah said.

Sanaullah and Niazi tabled at the Rock for “Religion Awareness Day” April 19. As they answered questions from student passersby, they realized just how helpful it could be to have an authority figure on campus to answer the tough questions and educate students who are ignorant about Islam.

“So many simple things can be clarified by a two-minute conversation,” Niazi said.