With a month left until graduation, students are preparing to celebrate completing their degrees and embarking on the next stage of their lives. But for international students, there’s still one final hurdle to legally working in the United States: a government process involving thick stacks of paperwork and plenty of uncertainty.

When Samir Al Rayes finished his undergraduate degree in business in 2010, he had to decide whether he wanted to stay in the United States to work or go back to his home country of Saudi Arabia.

The decision was simple for him. Either fill out a “mountain of paperwork” or go back to familiar territory.

“I would have to do my documents 90 days before I graduate, wait three months for it to process and then I’m given a year to find a job,” Al Rayes said. “Why go through all that? I have family back home, I have network connects back home and I am more familiar with the culture.”

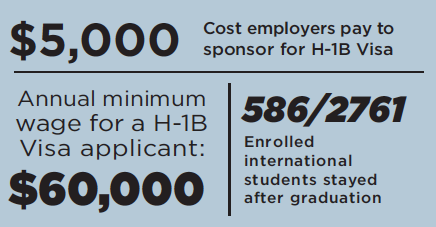

There were 2,761 international students studying at the University of Miami last year, and only 586 opted to stay in the United States to pursue work. The office of International Students and Scholars Services (ISSS) recorded this statistic by tallying the number of students who applied for the federal Optional Practical Training (OPT) program that allows foreign students to temporarily stay in the country after graduation to pursue work.

“All that trouble to stay?” Al Rayes said. “No, thank you.”

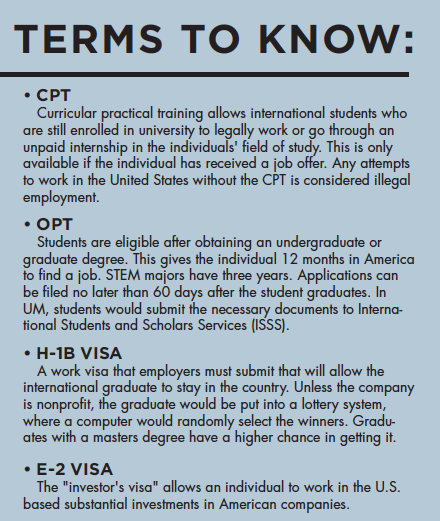

Those who decide to enroll in OPT would then face more uncertainty; OPT gives STEM majors three years to find employment in the United States and all other majors one year. Recent international graduates must find work within their declared majors. Al Rayes, a business major, developed an interest in public relations but wasn’t allowed to pursue it as a career.

OPT allows international graduates to find a job in the United States, but, in order to continue living in the country, they must have an employer sponsor for a H-1B visa, a temporary work visa. For employers, the sponsorship process can be costly.

Applying for a H-1B visa costs $5,000 in government fees, which includes filing for the form, fraud prevention fees and lawyer fees. Additionally, under the current regulation, the employer must pay the international graduate a minimum of $40,000 to $60,000 annually, varying by state and location. And those figures may grow larger.

President Donald Trump is reviewing a bill called the “Protect and Grow American Jobs Act” that would increase the minimum salary for international graduates to $100,000. Supporters of the bill argue that a higher cost for foreign workers would encourage companies to hire Americans.

Even with a H-1B visa, graduates aren’t guaranteed a job. The visa enters the international graduate into a lottery system with other prospective international employees. Last year, the government received 236,000 applications in just the first week before closing the doors, according to an April 3 New York Times report. A computer at the U.S. Citizen and Immigration Services (USCIS) then randomly selects those who would get the visa.

“You are paying all that money and putting in all that effort just for a chance,” said Kristi Mooti Persad, an alumna from Trinidad and Tobago. “There’s no magical formula for international students. You have to put yourself in the best possible position, and then it is left to chance.”

Mooti Persad decided to explore other options for staying in the country legally. She graduated in May 2011 with a bachelors in public relations and economics and decided to pursue her MBA in 2012. The lottery system prioritizes graduates with advanced degrees.

“International students have far less choices,” Mooti Persad said. “You don’t want to burn your OPT out into fields that won’t add to your portfolio and that won’t build your network.”

During her second OPT, once she graduated with her masters, Mooti Persad found another route through the E-2 investor visa, allowing an individual to stay in the United States based on investments. Mooti Persad then started her company, Premium Quality Group, which oversees other companies including Tio Fiesta, an event planning company.

“This creates a for-sure future rather than a chance,” Mooti Persad. “I had to show that I was adding value to the American economy … injecting money to make it stronger.”

Mooti Persad spent many “sleepless nights” wondering if she would be able to work in the country.

“We really have our work cut out for us,” Mooti Persad said. “We need to keep on top of the laws, the opportunities, finding the people willing to help you. We have to prove something to stay here.”

In addition to the uncertainty and long preparation that students must go through with USCIS, many struggle with fully assimilating into American culture. For many international students, staying in the United States to work after graduation is less than ideal.

“There are times where I don’t understand my professor because some have different accents,” said Zhang Ziyang, a junior with an undeclared major, in Mandarin. “If I struggle in class, the real world will eat me.”

“A lot of what the international students face is that companies don’t want to go through that trouble for an undergraduate,” said Natalie Song, who is now an assistant director of Asia-Pacific engagement with the Alumni Association. “It’s a big obstacle.”

Song bypassed the lottery system by working at the university. Working at any nonprofit institution grants a H-1B visa to international graduates for three years, renewable as long as the organization proves that the graduate’s employment aligns with his or her major.

Song called the visa lottery “a whole other monster.”

Similar to what Mooti Persad did, Song pursued a master’s degree in electronic media in 2014 to give her a higher chance to be recognized by prospective hirers.

“Before, having a degree from the United States was a golden ticket to a good company,” Song said. “Now it’s not good enough. Now you need a masters or working experience to boost your chance.”

While some graduates choose to return to their home countries, others are determined to stay despite the hurdles, confident that they can contribute to American society and that the opportunities that await will make it worth it in the end.

“It would have been easier to stay in Trinidad and have a stress-free life,” Mooti Persad said. “But I really wanted the opportunity to learn what the American dream is. To make a better life for the future.”