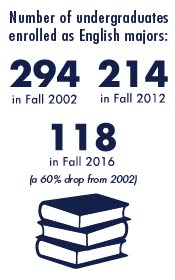

The number of undergraduate English majors dropped from 294 to 214 between 2002 and 2012, a decrease of approximately 27 percent over 10 years. By fall 2016, this number had dwindled to 118 according to the UM Fact Book.

For more than a decade, University of Miami students have gradually gravitated away from studying humanities in favor of fields perceived as more useful in attaining a job post-graduation.

This trend is not unique to UM. Under the pressure of student loans and rent payments, many students are looking for an immediate payoff to their education.

“I think you’re looking not just at local trends but larger cultural trends,” said Peter Schmitt, creative writing lecturer. “This is becoming an increasingly technology dominant society. More people are reading their screens and not reading books. Video games, the narratives of the actions in video games are replacing the narratives in novels.”

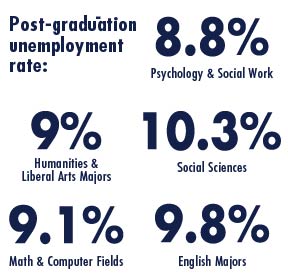

However, according to a 2010-11 study by the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, humanities and liberal arts majors actually have a post-graduation unemployment rate of 9 percent, approximately the same as in math and computer fields, psychology, social work and the social sciences.

Some parents, unaware or doubtful of the statistics, encourage their children to stay away from the humanities. Assistant English professor Lindsay Thomas encountered this when she completed her undergraduate studies at Colorado State University.

“I started out college as a pre-med major and kind of made my way through the sciences to the humanities,” Thomas said. “[My parents] had wanted me to take a straight and narrow path. They worried what I would be doing after graduation with an English degree … they wanted me to be a bit more focused in my major.”

While there is an impression that an English degree is useless without further education, professors and the evidence argue the contrary.

“There’s a massive disjunction between what students think you can do and what is actually possible,” English professor Timothy Watson said. “They go on to a wide range of careers or postgraduate degrees. The idea that all you can do is teach quite baffles me.”

However, professors at UM acknowledge that an English degree can be daunting due to the uncertainty of one’s future career path.

“Some people find comfort in the illusion of knowing what they’re going to be doing in five years,” creative writing professor Manette Ansay said. “Of course, some go on to graduate school and law school, but recently I just had someone go into the FBI. You just don’t know and that’s a little uncomfortable.”

Pamela Hammons, chair of the English Department, also considers parental discouragement and financial responsibilities a significant factor.

“Some studies have shown that parental influence makes a difference,” Hammons said. “If parents are concerned about their children’s career prospects, sometimes they steer their children away from the arts and humanities. Sometimes when people do that, they overlook the general problem of finding jobs at all. Issues of student debt are also a motivator to find a job quickly after school.”

The national unemployment rate was at 4.8 percent as of January 2017, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. This figure can be daunting, considering that the average student loan debt per graduate in 2017 is $26,872 for a public university and $31,710 for a private university, according to LendEDU.

Though the chances of getting a job after college are about the same, English majors are likely to earn a significantly lower salary than those who receive degrees in pre-professional and applied fields such as computer science and mechanical engineering. According to a study conducted by the Council of Graduate Schools, graduates entering those fields will likely earn $18,000 and $26,000 more per year respectively than those with an English degree.

According to a study conducted by the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, a recent college graduate with an English degree will earn around $32,000 and after a few years will earn an average of $52,000. However, a graduate degree holder will earn about $64,000.

The English Department is trying various new approaches to combat this decline. Since standard paper flyers have been unsuccessful in encouraging students to pursue an English major, the department has started using social media platforms and other nontraditional methods to get word out.

“I think creating forums where the capacity for critical thought and expressive power can be on display is important,” Director of Undergraduate Studies Joel Nickels said when discussing plans for spring 2017. “A number of students will be invited [to an undergraduate social] to give candidates for the best and worst sentences in the history of literature. It would be a way for students to lecture faculty for a change and to get up in front of their peers. They’ll compete for prizes, and it’ll be an initiative to show what English majors are capable of.”

Sophomore English and math double major Meg Kelley said students would be more attracted to the English major if the department “emphasized more that it’s a doable double major, so people can do something in addition that they think will be more practical in the working world.”

Despite the increasing tendency of students to gravitate toward pre-professional tracks, such as pre-medical or pre-dental, faculty and staff do not foresee the disappearance of an English major entirely.

“People will always need to study literature and language and the cultural and historical context in which those things gain meaning,” Hammons said. “These things can get reconfigured, but I don’t think that will change the fundamental importance of studying literature and learning to read and write critically.”