The University of Miami has big plans for on-campus housing over the next 10 years: constructing a new village for upperclassmen, tearing down and replacing the freshman towers and renovating every floor in the Mahoney and Pearson Residential Colleges. During the housing plan’s drafting, former UM President Donna E. Shalala prioritized the undergraduate population, according to Executive Director of UM Housing and Residential Life Jim Smart. But graduate students did not receive the same priority.

Although Smart said that a need for housing exists in the graduate student population, the current iteration of the 10-year housing plan does not allocate space for graduate students on or around campus.

The idea of graduate student housing at UM isn’t a novel one. Prior to July 31, 2009, graduate students were allocated 80 beds out of the 800 in the University Village. In January 2009, Patricia A. Whitely, vice president for Student Affairs, announced that those beds would be given to undergraduates and that graduate students would be unable to apply for housing on campus starting fall 2009.

“Graduate students are more capable of living off campus,” Whitely said in a 2009 report by The Miami Hurricane.

Edwing Medina, president of the Graduate Student Association (GSA), said that such a comprehensive housing plan should involve graduate students from the start; otherwise, they will not have a part in it anytime soon.

“Our concern at this time in the history of this university is that we will not have another major housing plan in place, after this one that is currently on the table, for at least 30-40 years,” Medina said. “If we don’t get this done now, the graduate students will be a non-issue as far as housing at the University of Miami for decades.”

Medina also sees the lack of graduates in the housing plan as a sign that the school does not heed the needs of its graduate student population adequately.

“I have sat in on many meetings where the highest administrators and the highest people of this university are in the room, and they talk about housing plans, and yet the graduate students are always an afterthought,” Medina said.

Whitely, however, said that the administration is “certainly aware” of the needs of graduate students, but undergraduates have a higher priority at the moment.

“The first phase of the [housing plan] is addressing undergraduates,” Whitely said in an email. “Graduate students were involved in our initial survey and focus groups. This issue has been brought up and discussed several times by GSA. If at any time we have the housing capacity to add graduate housing, we will do so. Presently, we do not have the capacity for our graduate housing.”

Although Whitely said she and her administrative staff practice an open-door policy when addressing student issues and concerns, Medina described conversations with UM about graduate housing as “one-sided” and “slow,” but said administration was still “receptive” to the issue, rather than closing off the conversation entirely.

The Age Factor

One of the main reasons why undergraduates have the higher priority is simply a matter of age, according to Smart.

“I don’t disagree that, in the cosmic scope of things, undergraduates probably should get a higher priority for housing than graduate students for no other reasons than age,” he said.

Smart said 17 and 18-year-olds coming into college are less competitive in the local realty market than 21 to 25-year-old graduate students. Contracts for renting apartments can’t be signed by people younger than 18; a parent or guardian would have to do so.

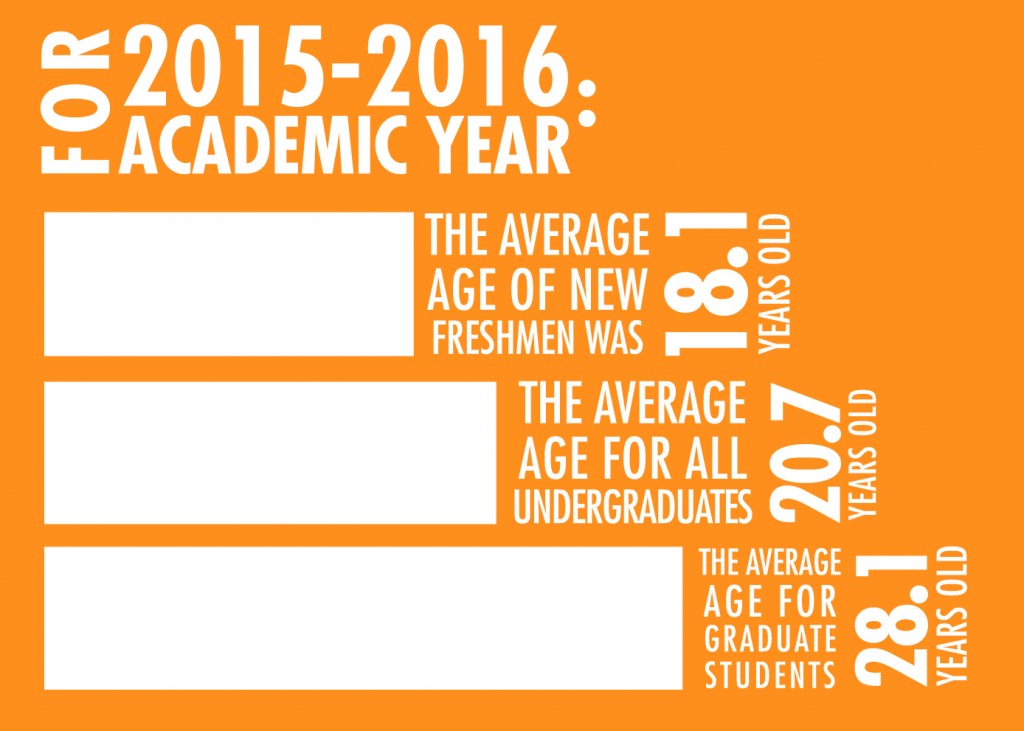

According to UM’s 2015-16 Fact Book, the average age of new freshmen for that year was 18.1 years old. For all undergraduates, the average age was 20.7 years old.

For graduate students, the average age was 28.1 years old. Numbers from the book reflect counts from the fall semester. At the same time, 94 percent of all undergraduates were younger than 24 years old. For graduate students, 73 percent were younger than 29 years old.

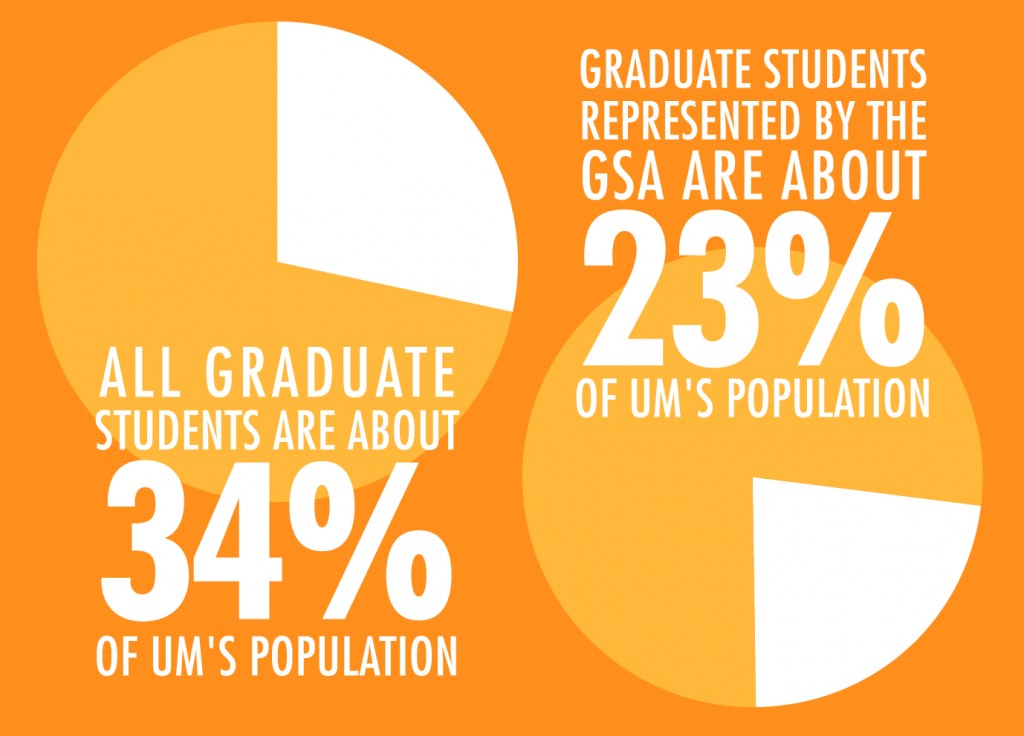

The book states that 11,123 undergraduates and 5,725 graduate students attended UM. Of the 5,725 graduate students, 3,921 are directly represented by the GSA. Graduate students at the School of Law and the Miller School of Medicine are not directly represented by the GSA. Medina said more than 650 undergraduates are 25 and older, while 1,285 graduate students – not including law and medical students – are younger than 24. That’s about a third of the GSA’s graduate population.

“This essentially debunks the argument that the university uses to say that they must provide housing to [undergraduates] simply because they are a younger, more vulnerable population,” Medina said.

Search for Space

Another factor limiting the prospects of graduate housing is the lack of space on the Coral Gables campus, which Medina said he understood.

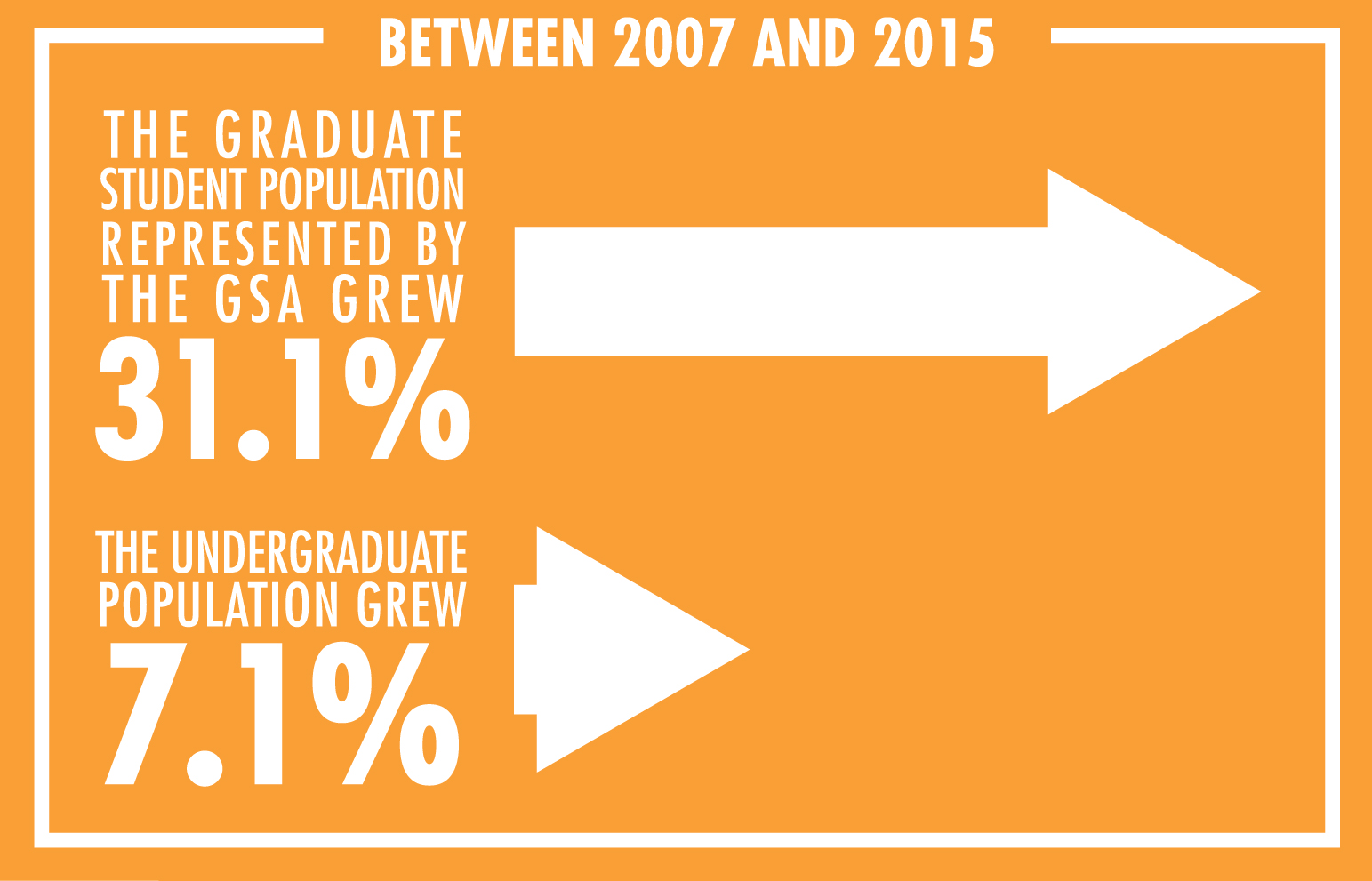

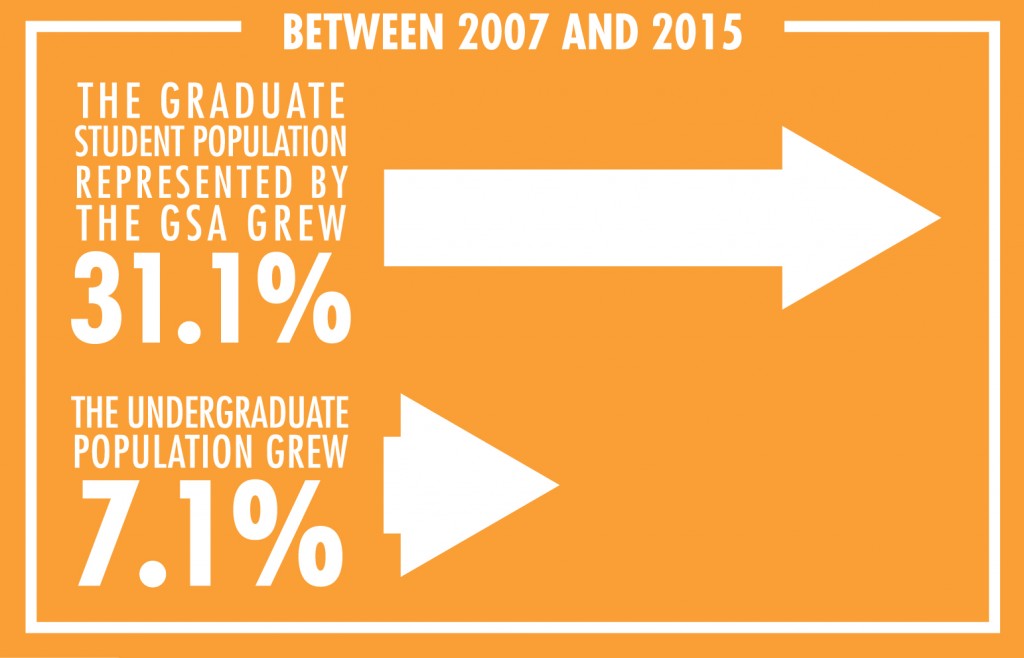

However, a growing graduate student population should be prompting more action from the administration, Medina said. In 2007, the population was 2,991. That number climbed to 3,327 by 2011, and again in 2015 to 3,921. This shows a 31.1 percent increase in the population from 2007-2015. The undergraduate population grew by just 7.1 percent during the same time.

“It says to the graduate students that you’re welcome to come and study here, you’re welcome to come and teach our classes, you’re welcome to come and do the university’s research, but when it comes to finding a community here that we have physically created for you, that is not as on the table as other options,” Medina said.

More than 900 graduate students come from outside the U.S. Upon landing in Miami, they do not have credit histories or social security numbers. This makes signing paperwork for apartments difficult or more expensive, according to Utsav Sharma, a Ph.D. student at Miller who conducted his undergraduate studies in the U.S. after coming from India.

Smart stressed that the university has not said “no” to the idea of graduate student housing, but market research conducted by the housing department showed a greater need for housing came from undergraduates, especially freshmen.

“We’re really building from the first-year experience forward,” Smart said. “At some point, we might get around to looking at the graduate school program, but that’s at least phase four [of the housing plan], and we’re not there yet.”

On-campus housing has a capacity of 4,344 beds, according to the 2015-16 Fact Book. Only 4,013 beds were taken by the fall semester, which is 92.3 percent. When asked about the potential space, Smart noted that empty rooms are reserved for students with medical emergencies, roommate complications or issues with their current room, like a broken air conditioner.

Although having every room filled would be beneficial for housing’s bottom line, it would negatively affect undergraduate student life. The space, then, cannot be somehow converted to graduate housing, according to Smart. Smart also said that 92.3 percent capacity is an outlier; housing hasn’t operated below 97 percent capacity – around 4,210 beds – over the past five years.

Ideas for Graduate Housing

Smart said he has not personally let the idea of graduate housing sit by the wayside.

“If I were playing the Vegas odds, we will wind up doing something for graduate students sooner – meaning the next three to five years – rather than later,” Smart said.

He imagines graduate student housing taking the form of one-year, transitional residencies due to collected data showing a demand for short-term housing. This configuration would provide 200-250 rooms to first-year, non-Floridian graduate students to help them adjust to living in Miami.

“They don’t know anything about Miami,” Smart said. “They, too, like freshmen, are at a disadvantage in terms of finding a space to live.”

Smart has this plan waiting in his back pocket just in case a donor or someone higher up in the administration decides to make graduate housing a bigger priority for the university. It is the higher-up administration, not Smart, who decides what ultimately gets implemented with regard to housing. This includes people like the provost, the president and the Board of Trustees. Smart can only provide recommendations and information to the higher-ups, who look at the welfare of every aspect of the university.

“Senior decision makers have a lot of people with their hands out asking for resources to do very worthy things,” Smart said.

The idea envisioned by Smart, however, still frustrates Medina.

“It still seems like the university is not making a point to set aside some batch of space for the graduate students,” he said. “Our frustration with that is that it is very unlikely that unless you dedicate some space for graduate students, there will be any space left over.”

Medina said that if first-year graduate students are allotted the limited space, none would be left over for graduate students further along in their education.

To help advocate for graduate housing, the GSA developed a three-pronged plan for how UM could tackle the issue: transitional housing, conference housing and temporary residencies for students enrolled in UM’s online graduate programs.

The transitional housing idea resembles the one proposed by Smart, providing at most one year of housing for incoming first-years.

Conference housing would address an aspect that both Medina and Smart said UM lacks. When an event invites people from other parts of the U.S. or the world to UM for multiple days, third-party hotel services must be used, adding to the cost of hosting. Conference housing owned by UM would address that issue.

Finally, housing for online students involves weekend or week-long stays for graduate students. This would provide an opportunity to have a residency or face-to-face meetings with professors.

All three would take place in a single structure with 400-500 beds, according to Medina.

“If you were to build a creative structure that could serve those variable purposes and then administer it, we believe that it would be a profit center for the university [and would] fulfill the academic, social and personal wellbeing of students living there, and it would fulfill the research and conference expectations of any research university,” Medina said.

The facility, he proposed, could be placed somewhere between the Miller School of Medicine, the Coral Gables campus and RSMAS along the Metrorail line.

Cost of Housing in Miami

Although the idea of housing along the Metro intrigued Smart, he wondered about how marketable the idea is. One aspect in particular is the location of these possible sites. Land around the Metro has become pricey according to Smart, and places such as Coconut Grove, Brickell, Douglas Road and Downtown are rapidly being bought by developers already.

“If the [Board of Trustees] is going to agree that this is a priority, I think the GSA is going to have to make a better case than they have thus far that there is a need for graduate student housing that can’t be fulfilled by the local market,” Smart said.

The local market, however, can be expensive. According to myapartmentmap.com, the average rent for a one-bedroom apartment within 10 miles of UM is $1,789. A two-bedroom apartment can go for $2,470 per month, and a three-bedroom for $3,064 per month. A studio costs $1,610 per month, on average. Roommates, however, can help split costs. The average rent of apartments in Florida is $1,657.

Jordan Balke, parliamentarian of the GSA, said that stipends some graduate students receive from the school are not enough to cover the costs. As a Ph.D. student at Miller, Balke receives about $28,000 per year, about the highest stipend any graduate student at UM can get. She described her stipend as “enough to live off.”

Areas outside Coral Gables offer both higher and lower rent rates, depending on the location.

Considering the boom in development around Miami, Smart said the cost of the GSA’s plan may outweigh the benefits.

“We can’t build housing to cover the costs. It’s too expensive in Miami for construction given what students want to pay and occupancy levels,” Smart said.

Moving Forward

Medina has been president of the GSA during both Shalala and President Julio Frenk’s administrations. Upon Frenk’s arrival, Medina sensed more openness in conversations with the administration.

“When President Frenk and his designees are in the room, the conversation feels more welcome, and I think there is, in general, a recognition that graduate students matter with this new president,” Medina said. “He and his wife are very graduate-student welcoming and friendly, and so there may be something in the next three to five years.”

Although the idea of graduate student housing is very much still up in the air, Smart said he sees the GSA’s advocacy as a good thing.

“We should continue to look at the idea of graduate housing,” Smart said. “At some point, that would be in students’ best interests. When the university will have the resources to move that up on the priority list is still an open question.”