The Cuban Heritage Collection (CHC), an on-campus, archival hub for all things Cuba, received a $2 million gift from the Goizueta Foundation, a philanthropic organization that helps fund educational and charitable institutions.

This gift was announced shortly before the opening ceremonies of the annual Week of Cuban Culture, held by the Federation of Cuban Students (known as FEC, for its name in Spanish), which promotes Cuban history and traditions.

But UM’s relationship with Cuba extends beyond this week or this collection. In fact, since it opened its doors in 1925, the university has welcomed Cuban students and scholars alike, and they have significantly contributed to campus culture. Aside from the CHC’s academic contributions, FEC members have helped weave their heritage into UM’s social fabric.

The Goizueta Foundation’s gift came as part of the Momentum 2 fundraising campaign. Half of the gift, $1 million, will go to the Goizueta Foundation’s Graduate Fellowship Program at UM, which will allow the CHC to award research opportunities to doctoral students across the country.

The foundation also challenged the University of Miami to raise $500,000 in support of CHC. When this is achieved, the foundation will donate $1 million to support the CHC’s mission to preserve and digitize primary and secondary sources about Cuba.

The foundation itself is named after Roberto Goizueta, the Cuban-born chairman of the Coca-Cola Company, who died in 1997. The addition that houses the CHC was inaugurated in 2003 after a $2.5 million donation from the foundation.

Open door origins

In 1926, UM had an open door for exchanges with Cuba and brought Cuban students and professors to study and teach on campus. In 1928, the first Latin-American student, Carlota Sarah Wright, came from Santiago, Cuba.

Two of the Hurricanes’ eight wins during the football teams’ inaugural season were against the University of Havana. One was at home on Thanksgiving Day and the other was in Havana on Christmas Eve. UM’s swimming team also competed against Cuban teams in its early years.

When the U.S. placed an embargo against Cuba in 1962, there was an influx of professionals and students in exile who chose to continue their education at the University of Miami.

During this time, the Miller School of Medicine created the Cuban Refugee Program to prepare Cuban physicians for the Educational Council for Foreign Medical Graduates. Cuban lawyers and teachers were provided training courses to prepare for jobs in Miami.

In 1965, UM established the Cuban Cultural Center at the Koubek Memorial Center, which still exists today. The center helps recently arrived Cuban exiles adjust to life in the United States by providing vocational and cultural programs.

With the recent lifting of the embargo, Lillian Manzor, associate professor in the College of Arts and Sciences and director of Cuban Digital Archives, believes there won’t be much change anytime soon with regards to going to Cuba.

“I can see exchange students coming here but, within the next year or two, UM students won’t go there,” she said. “Since we’re from Miami, our students are more at risk … Cuba guards their educational system like UM guards its students.”

Manzor, who is originally from Cuba, left the island in 1968 and completed her undergraduate career at UM. She is an associate professor at the Department of Modern Languages and has worked with Cuban students in her classes and in her office. One of those students is sophomore Melissa Hurtado, who came from Cuba in 2002 with her mother.

“[Manzor] has helped me in so many ways,” Hurtado said. “We discuss lots of Cuban-related things, and it’s a really important sort of familiarity for me on campus.”

Hurtado added that she views campus as a more “international, Americanized place in Miami,” especially since she commutes from Hialeah – a local community heavily populated by Cubans.

“Even when I speak Spanish on campus, it’s a lot more formal, neutral, for everyone to understand me,” she said. “I don’t use strong Cuban slang, for example.”

Hurtado says the Pollo Tropical restaurant in the food court serves as the extent of Cubans and Cuban-Americans’ on-campus influence. Unlike Hurtado, however, Manzor senses a strong Cuban presence on campus.

“Our student body is representative of what’s going on,” Manzor said. “You have the ones who came as babies, the ones on the visa programs, the ones who come through a third-world country.”

Manzor also plays a large role in cultural exchanges between Miami and Cuba. In 2001, she helped co-organize an international monologue performance festival with UM and Florida International University (FIU) and brought 29 Cubans to perform.

In May, Manzor will help host a conference to discuss the cultural situation in Cuba. Topics will include how children’s literature captures everyday life in a communist country and how actors are navigating the bureaucracy to be able to perform.

Still, Manzor says UM is falling behind on its relationship with Cuba because, although the embargo should have cut all ties with the island, some Ivy League schools, like Brown University, still collaborate with Cuba.

“If there’s an institution that should have relations, it needs to be us,” Manzor said. “If they can work it out, why can’t we?”

As of right now, UM has blacklisted any Study Abroad programs to Cuba. Hurtado tried to go for a semester but was told she would have to withdraw from school and “figure out the credits on my own.”

“Other universities don’t do that, so I think that the relationship that UM has with Cuba is very related to the relationship that the Miami exile community has with Cuba,” Hurtado said.

Home away from home

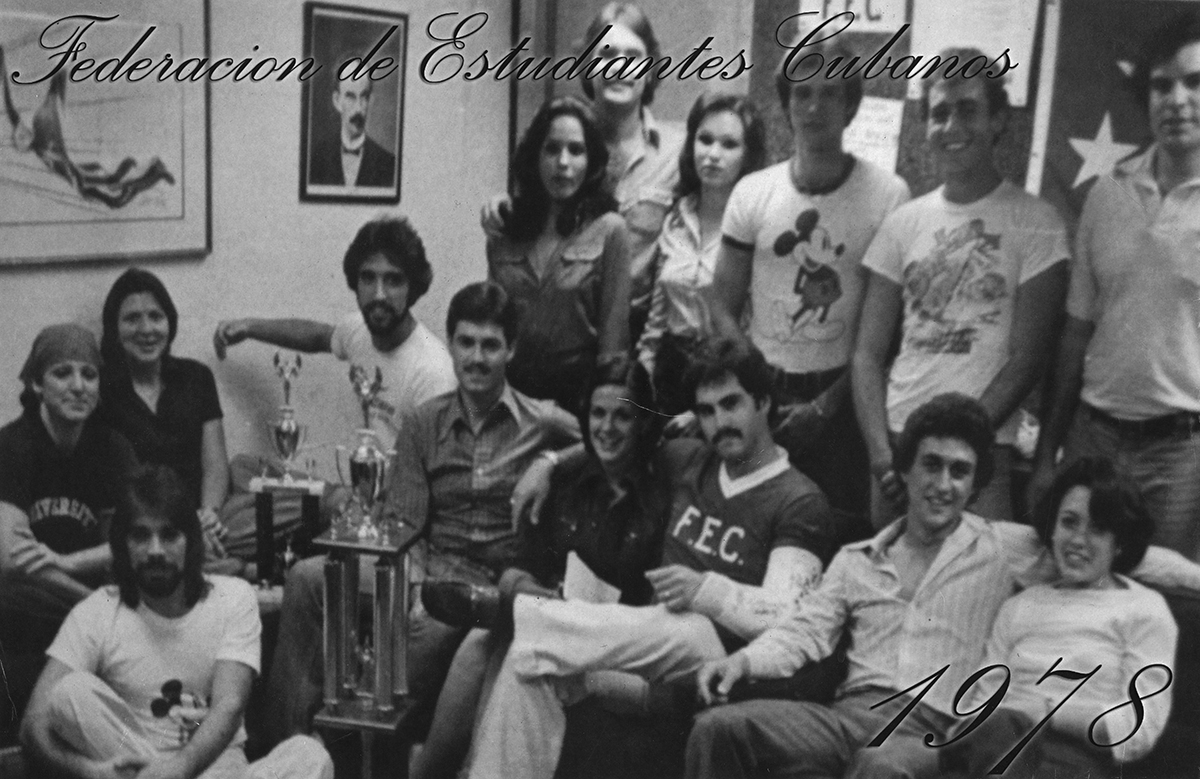

Until a formal Study Abroad program to Cuba is realized, FEC is continuing its history of spreading cultural awareness. Since 1967, FEC has offered a space for Cubans and Cuban-Americans to find a home at UM.

Fifth-year seniors and brothers Alejandro and Eduardo Lamas immigrated to Miami from Cuba in 2007. They joined FEC not only to celebrate their culture, but also to integrate themselves with the campus community.

“FEC was the first organization I joined at UM … with them I learned about school pride,” Eduardo said.

Alejandro says FEC has helped him feel comfortable as a Cuban student on campus.

“I’ll always be proud to be Cuban, and the fact that I am able to show my culture on campus without discrimination makes me feel happy and proud,” Alejandro said.

The club serves as a bridge for the campus community to learn about Cuban culture and its influence on Miami through events throughout the year, according to Daniela Lorenzo, FEC’s president-elect.

“A lot of our events, like Honorary Cuban and Week of Cuban Culture, are really popular, and those that know about it look forward to it every year,” she said. “Cubans settled [in Miami] and made this city what it is … knowing the culture, the food, the traditions, etc. are incredibly important in order to fully enjoy and appreciate [Miami].”

FEC started out with political and military aims, with members going to the Everglades every weekend to train in a military capacity, according to Gladys Gomez-Rossie, the FEC’s adviser since 1998. She has been working in Richter library since 1967.

“Back then, students came from Cuba and their idea was, ‘My parents got me out of Cuba, I want go back and fight for Cuba,’” she said. “But later on, the university told them that in order for them to be given an office, they needed to become a cultural organization, not political.”

For Gomez-Rossie, the mention of Week of Cuban Culture conjures up a wide smile and clear excitement. She came to the U.S. as part of Operation Pedro Pan. During this exodus, thousands of Cuban youths arrived in Miami without their parents, due to the fear many Cuban parents had that Castro would indoctrinate their children.

Although Gomez-Rossie was part of a mass exodus from her home country, sharing her Cuban heritage is important to her.

“It’s important because it’s showing off on campus who we are,” she said. “You’re always happy to share your culture, you want to share what you think is great … because here you have people from all over the rest of the world.”

William Riggin contributed to this report.